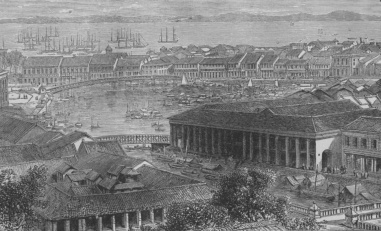

Wallace in Singapore

Alfred Russel Wallace arrived in Singapore on the Peninsular and Oriental Company's steamship on 18 April 1854 (not the 20th as was believed in the past). He had no precise route or plan, just to collect natural history specimens for sale in London. But Wallace's adventures and scientific discoveries would change the world in ways no one could have predicted.

Alfred Russel Wallace arrived in Singapore on the Peninsular and Oriental Company's steamship on 18 April 1854 (not the 20th as was believed in the past). He had no precise route or plan, just to collect natural history specimens for sale in London. But Wallace's adventures and scientific discoveries would change the world in ways no one could have predicted.

At first he stayed for a week in a hotel. He lost no time in hunting for birds and insects.

I examined the suburbs, and soon came to the conclusion that it was impossible to do anything there in the way of insects, for the virgin forests have been entirely cleared away for four or five miles round (scarcely a tree being left), and plantations of nutmeg and Oreca palm have been formed.

Wallace predicted that if the forest clearing continued in Singapore the result would be that "countless tribes of interesting insects become extinct". S14 As he travelled throughout the region he saw that many natural environments were fast disappearing. He pleaded that their biodiversity should be surveyed as quickly as possible before it was lost forever.

If this is not done, future ages will certainly look back upon us as a people so immersed in the pursuit of wealth as to be blind to higher considerations. They will charge us with having culpably allowed the destruction of some of those records of Creation which we had it in our power to preserve; and while professing to regard every living thing as the direct handiwork and best evidence of a Creator, yet, with a strange inconsistency, seeing many of them perish irrecoverably from the face of the earth, uncared for and unknown. S78

Such remarks certainly make it sound as if Wallace was a pioneer of nature conservation.

Such remarks certainly make it sound as if Wallace was a pioneer of nature conservation.

To get closer to the remaining forests, Wallace moved into the centre of the island to stay with a French Roman Catholic missionary at St Joseph's in Bukit Timah district. Wallace trekked daily into the forest covered hilltops in the area and collected thousands of insects and birds. He heard the roars of man-eating tigers in the forest. He spent a week on the nearby islet of Pulau Ubin and witnessed the dramatic Chinese Riots of 1854 that left hundreds of people dead.

During his eight-year stay in the archipelago, covering parts of modern Malaysia, Singapore, East Timor and Indonesia, Wallace made many journeys and covered thousands of miles.

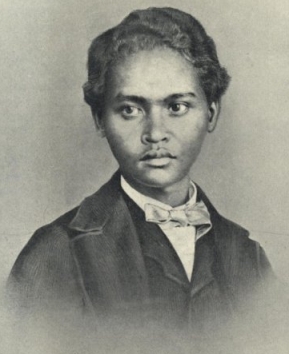

Along the way he also observed the many peoples of the region. He learned to speak Malay with the help of his long-time assistant from Sarawak, Ali. (See photograph below. The only detailed historical study of Ali has recently been published, here.) Wallace's Malay dictionary is included on this website, here. In addition to his many discoveries and adventures, Wallace came to love the infamous durian fruit. He described it as "A thick glutinous, almond-flavoured custard is the only thing it can be compared to, but which it far surpasses." Indeed, he said, "to eat Durians is a new sensation, worth a voyage to the East to experience". See his eye-watering account with durian, here. When in town Wallace made extensive use of the Singapore Library. We have digitized a catalogue of the library here.

Wallace stayed several times in Singapore, in total 228 days as we have calculated.  He later lost some letters and a notebook that described his time in Singapore. So when he came to write his great book of travels, the Malay Archipelago (1869), Singapore was mostly described from memory. Although writing from memory, Wallace nevertheless wrote one of the most charming and apt descriptions of mid-nineteenth-century Singapore, see here.

He later lost some letters and a notebook that described his time in Singapore. So when he came to write his great book of travels, the Malay Archipelago (1869), Singapore was mostly described from memory. Although writing from memory, Wallace nevertheless wrote one of the most charming and apt descriptions of mid-nineteenth-century Singapore, see here.

One rare manuscript sheet Wallace wrote in Singapore survives today in London's Natural History Museum: 'The Chinaman at Singapore'.

In March 1856 Wallace was back in Singapore before setting off on a new expedition. He wrote to his brother-in-law the London photographer Thomas Sims:

I quite enjoy being a few days at Singapore now. The scene is at once so familiar & strange. The half-naked Chineese coolies, the neat shop keepers, the clean, fat, old, long-tailed merchants, all as busy & full of business as any Londoners. Then the handsome Klings, who always ask double what they take, & with whom it is most amusing to Bargain. The crowd of boatmen at the Ferry, a dozen begging & disputing for a farthing fare, the Americans, the Malays & the Portuguese make up a scene doubly interesting to me now that I know something about them & can talk to them in the general language of the place. The streets of Singapore on a fine day are as crowded & busy as Tottenham Court Road & from the variety of nations & occupations far more interesting. I am more convinced than ever that no one can appreciate a new country in a short visit. After 2 years in the country I only now begin to understand Singapore & to marvel at the life and bustle, the varied occupations, & strange population, which on a spot which so short a time ago was an uninhabited jungle. A volume may be written on Singapore without exhausting its singularities.

Wallace asked his London agent to assist in selling two boxes of books to help his a young friend in Singapore named George Rappa. "He is the son of the collector who lived many years at Malacca, but has quarrelled with his father & is very badly off." Wallace's assistance may have helped because, as this project has recently discovered, in 1859 Rappa became a partner of Philip Robinson, founder of Robinson and Co., the oldest department store in Singapore.

Wallace's collecting in Singapore was decades before the first systematic catalogues of Singapore's biodiversity. Therefore his collections form some of the oldest records of what species originally inhabited the island. Some of his collections were published, others have remained locked away in his notes and notebooks. All together these materials provide one of the earliest snapshots of Singapore's original biodiversity.

During the same visit Wallace jotted the following into his notebook:

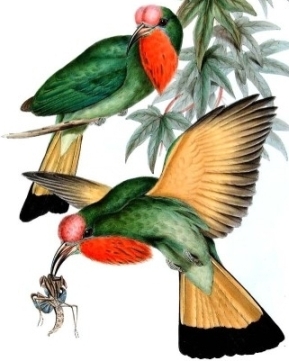

Bee Eater (Merops)

This like a swallow but slower, very graceful circles round & settles on sticks & twigs & posts. Seizes insects on the wing & rests to swallow them cleans its bill against the perch. Chirps or twitters during flight.

This was the Blue-tailed Bee Eater (Merops philippinus), below.

Other birds collected by Wallace in Singapore include the Red-bearded Bee-eater (Nyctyornis amictus) which he called "one of the loveliest of Eastern birds". Above right.

There was also the "the beautiful azure and black Irena puella" or the Asian Fairy-bluebird. (below left)

One of the commonest birds was the Red-crowned barbet (Megalaima rafflesii) (above right).

Of the butterflies was the Elymnias undularis (below). Some of the thousands of beetles Wallace collected in Singapore are below, right.

Just before departing from Singapore, and the East, for the last time in February 1862, Wallace had a photograph taken of himself and a friend. An edited version was published in the biography of Wallace in 1916. It is the only photograph of Wallace taken during his travels. All modern artistic representions of Wallace in the field in the East follow this photograph as a model. This is, however, quite incorrect. Wallace is here dressed as a gentleman about to board the steamer with his first-class ticket. His appearance here has nothing to do with how he dressed in the field.

Just before departing from Singapore, and the East, for the last time in February 1862, Wallace had a photograph taken of himself and a friend. An edited version was published in the biography of Wallace in 1916. It is the only photograph of Wallace taken during his travels. All modern artistic representions of Wallace in the field in the East follow this photograph as a model. This is, however, quite incorrect. Wallace is here dressed as a gentleman about to board the steamer with his first-class ticket. His appearance here has nothing to do with how he dressed in the field.

Wallace also left behind his young English collecting assistant, Charles Allen, who eventually settled in Singapore. Allen married and raised a large family and became the manager of of an estate located in what is now Geylang. The estate grew and processed lemon grass to make citronella oil which was used in soaps and insect repellent. In 1887 Allen became owner of the estate. The poor working-class London boy Wallace had brought out as an assistant finally made his fortune in the East. Allen died in 1892. Allen's daughters married well, one even to the architect of Singapore's famous Raffles Hotel.

Today Wallace is featured at the splendid Wallace Education Centre located at Old Diary Farm. One half is devoted to the Wallace Environmental Learning Lab (WELL) and there is a 1km "Wallace trail" through the forest nearby where he once collected. Finally, there is a small road named in his honour, Wallace Way.

There is a wealth of further information about Wallace's time in Singapore and the specimens of wildlife he collected here available through Wallace Online, see here.

The most detailed account of Wallace in Singapore is Chapter 3 of Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the discovery of evolution by Wallace and Darwin. (2013)

John van Wyhe