STANFORD'S COMPENDIUM

OF

GEOGRAPHY AND TRAVEL

FOR GENERAL READING

BASED ON HELLWALD'S 'DIE ERDE UND IHRE VÖLKER'

TRANSLATED BY A. H. KEANE, M.A.I.

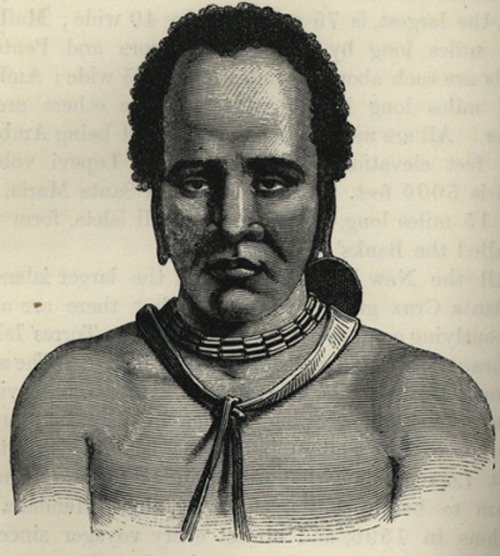

NEW ZEALAND CHIEF.

Frontispiece.

STANFORD'S COMPENDIUM OF GEOGRAPHY AND TRAVEL

BASED ON HELLWALD'S 'DIE ERDE UND IHRE VÖLKER'

AUSTRALASIA

EDITED AND EXTENDED

BY ALFRED R. WALLACE, F.R.G.S.,

AUTHOR OF 'THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO,' 'GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF ANIMALS,' ETC.

WITH

ETHNOLOGICAL APPENDIX BY A. H. KEANE, M.A.I.

MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

EDWARD STANFORD, 55 CHARING CROSS, S.W.

1879

PREFACE.

THE present volume differs somewhat from the rest of this series of works, in consisting almost wholly of new matter. This was rendered necessary by the meagre treatment of Malaysia, Australia, and the Pacific Islands, in Hellwald's book, which was, as regards this portion of it, on so small a scale that I found it impossible to enlarge or add to it without rewriting the whole. The few short paragraphs devoted to the Exploration, to the Natural History, and to the Colonies of Australia, were altogether inadequate as the basis of an English geographical work; and the same may be said of the equally brief notices of the large and important islands of the Malay Archipelago. As an example, I may refer to the account of Borneo, in which the only reference to the two English settlements is as follows:— "while the English have made more or less permanent settlements in Labuan and Sarawak."

This paucity of available material has rendered it necessary for the volume to be practically rewritten, and I have thus been enabled to make it as complete a "Compendium" of the geography of Australasia as was possible within the prescribed limits. I have endeavoured to secure uniformity of treatment by giving the same kind, as well as the same amount, of information, in the case of corresponding islands and colonies, wherever the accessible

materials admitted of it, and to proportion the amount of detail in the description of each colony, island, or group of islands, to their intrinsic importance and general interest. Separate chapters are devoted to the Natural History, the Aborigines, and the Geology, of Australia—the latter being, I believe, the first attempt to give a popular but accurate sketch of the present state of knowledge of this interesting but extremely difficult subject. The characteristics and habits of the various races of mankind, the relics of prehistoric man that occur in the Pacific Islands, and the more interesting features of the natural history of the different regions and great island groups, have all been briefly described.

With every wish to utilise the translation of Hellwald's book as far as possible, I have only been able to do so to the extent of little more than one-tenth part of the present volume.

Notwithstanding the great number of islands and groups comprised within the area treated of, none of any importance have been left without proportionate notice; and I venture to hope that the volume will be found to contain a condensed but accurate summary of geographical information on one of the least known, but most varied and most interesting, of the great divisions of the earth.

CROYDON, January 31, 1879.

LIST OF WORKS USED IN PREPARING THIS VOLUME.

Australia and New Zealand.

GORDON and Gotch, Australian Handbook: 1878.—Silver's Australia and New Zealand. 2d Edition: 1874.—Encyclopædia Britannica, article 'Australia.'—Angas, G. F., Australia, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.—Angas, G. F., Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand: 1847.—Lang, History and Statistics of New South Wales: 1875.—Russell, Climate of New South Wales: 1877.—Hayter, Notes on the Colony of Victoria: 1876.—Harcus, South Australia: 1876.—Müeller, Select Plants of Victoria: 1876.—Sturt, Interior of South Australia: 1833.—Sturt, Central Australia: 1849.—Mitchell, Expedition in Interior of New South Wales: 1839.—Mitchell, Expedition in Interior of Tropical Australia: 1848.—Forrest, Explorations in Australia: 1875.—Warburton, Journey across the Western Interior of Australia: 1875.—Leichardt, Journal: 1847.—M'Douall Stuart, Explorations in Australia: 1864.—Wills, J. E., Exploration from Melbourne to Gulf of Carpentaria: 1863.—Giles, Travels in Central Australia: 1875.—Giles, Journey from South to West Australia, Journal of Royal Geographical Society: 1876.—Howitt, Land, Labour, and Gold: 1858.—Trollope, A., Australia and New Zealand: 1873.—Hochstetter, New Zealand: 1867.—Taylor, Rev. R., New Zealand and its Inhabitants: 1870.—Taylor, Rev. R., New Zealand, Past, Present, and Future: 1868.—Journal of Royal Geographical Society.—Proceedings of Royal Geographical Society.—Clarke, Rev. W. B., Remarks on the Sedimentary Formations of New South Wales.—Wood, Geological Observations in South Australia.—Strzelecki, Physical Description of New South Wales: 1843.—Smith, R. Brough, Geological Map of Australia: 1878.—Reports of the Geological Survey of Victoria.—Hooker, Sir Joseph, Essay on Flora of Australia.—Hooker, Sir Joseph, Flora of New Zealand.—Transactions of Ethnological Society of London, vol. 3. Oldfield on Australian Aborigines.—Transactions and Proceedings of New Zealand Institute.—Wallace, Geographical Distribution of Animals.

Malaysia.

Jagor, Travels in the Philippines: 1875.—Crawfurd, J., Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands.—Geografia Philippina (Spanish official maps of Philippines).—Wallace, A. R., The Malay Archipelago: 1869.—Bickmore, A., Travels in the East Indian Archipelago: 1868.—St. John, S., Life in Forests of Far East: 1863.—Earl, G. W., The Eastern Seas: 1837.—Motley, Letters from Borneo, in Hooker's Journal of Botany, 1850-56.—Consular Reports on Java, Borneo, and the Philippines.—Geographie van Nederlandsch-Indie, Martinmas Nijhoff.

Melanesia, Polynesia, and Mikronesia.

Brenchley, Cruise of the Curaçoa: 1873.—Erskine, Islands of the Western Pacific: 1853.—Turner, Rev. G., Nineteen Years in Polynesia: 1861.—Hopkins, Manley, Hawaii: 1862.—Seemann, B., Mission to Viti: 1862.—Pritchard, W. T., Polynesian Reminiscences: 1866.—Wood, C. F., A Yachting Cruise in the South Seas: 1875.—Campbell, A., A Year in the New Hebrides: 1873.—M'Gillivray, Voyage of the Rattlesnake: 1852.—Earl, G. W., Papuans: 1853.—Garnier, Jules, Nouvelle Caledonie et Tahiti.—Belcher, Lady, The Mutineers of the Bounty.—Markham, New Hebrides, in Journal of Royal Geographical Society: 1872.—.Palmer, Easter Island, in Journal of Royal Geographical Society: 1870.—New Guinea (Papers on), in Geographical Magazine: 1873-77.—New Guinea (Papers on), "Colonies:" 1876-78.—New Guinea, Galton on Micklucho Maclay's Discoveries, in 'Nature': 1876.—New Guinea, Moresby, Captain J., Discoveries in Eastern, Journal of Royal Geographical Society: 1875.—New Guinea, Stone, O. C., on Port Moresby and Natives, Journal of Royal Geographical Society: 1876.—New Guinea, D'Albertis on Fly River, Proceedings of Royal Geographical Society: 1876.—New Guinea, Dr. Comrie, Anthropological Notes, Journal of Anthropological Institute: 1876.—New Guinea, Rev. W. G. Turner on Ethnology of the Motu, Journal Anthropological Institute: 1878.—Also various Papers referring to discoveries of Maclay, Meyer, D'Albertis, and to the Ethnology and Natural History of New Guinea, in 'Nature,' vols. viii. ix. xiii. xiv. xv. and xvi.—Admiralty Islands, Mosely, H. N., on Inhabitants of, Journal of Anthropological Institute: 1877.—Ranken, W. L., on the South Sea Islanders, Journal of Anthropological Institute: 1877.—Forbes, Dr. Litton, On the Navigator Islands, Proceedings of Royal Geographical Society: 1877.—Brown, Rev. G., On New Britain and New Ireland, Journal of Royal Geographical Society: 1877.—Consular Reports on Fiji, Sandwich, and Society Islands.

London, Edward Stanford, 55, Charing Cross. S.W.

CONTENTS.

| AUSTRALASIA. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| PAGE | |

| Definition and nomenclature—Extent and distribution of lands and islands—Geographical and physical features—Ocean depths—Rates of mankind—Zoology and botany—Geological relations and past history—Geographical divisions | 1 |

| AUSTRALIA. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE OF AUSTRALIA. | |

| Dimensions, form, and outline—Contour of the country—Mountains and table-lands—The interior—Rivers—Climate of Australia—Climate of New South Wales—Winds—Snow—Droughts and floods | 13 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE NATURAL HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA. | |

| Characteristics of Australian vegetation—Botanical features and relations of the Australian flora—The external relations of the Australian flora—General features of Australian zoology—Mammalia—Birds—Reptiles, fishes, and insects | 36 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE GEOLOGY AND PAST HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA. | |

| General considerations—Palæozoic formations—Mesozoic formations—Tertiary formations—Quaternary or Post-pliocene deposits—Ex- |

| tinct volcanoes and their products—Geological features of the gold mines—The "oldest" drifts—The "older" drifts—"Recent" drifts—Quartz reefs—Probable past history of Australia—Origin of the desert sandstone—Origin of the drifts and alluviums | 64 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINES. | |

| Physical characteristics—Mental qualities—Clothing, dwellings, and food—Weapons and tools—Occupations and amusements—Government and war—Religion; ceremonies of initiation, marriage, and burial—Language—Probable origin of the Australian aborigines | 86 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE BRITISH COLONISATION OF AUSTRALIA; | |

| THE DISCOVERY, EXPLORATION, AND MATERIAL PROGRESS OF THE COUNTRY. | |

| Outline of Australian colonisation—Early history, discovery, and maritime exploration of Australia—Inland exploration—Early explorations of Hume, Sturt, and Mitchell—Journeys of Eyre and Sturt to the desert interior—Leichardt and Kennedy in the north-east—Gregory in the north-west—M'Douall Stuart's journey across the continent—The fatal expedition of Burke and Wills—Establishment of the telegraph line to the north coast—The western deserts traversed by Giles, Warburton, and Forrest—General result of these explorations—Growth of the population—Agriculture—Mineral wealth—Commercial activity—Railways and telegraphs | 107 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE COLONY OF NEW SOUTH WALES. | |

| Origin, geographical limits, and area—Physical features—Climate, natural history, and geology—Colonisation, population, etc.—Productions, trade, shipping, etc.—Roads, railways, and telegraphs—Political and civil divisions—Alphabetical list of counties—Cities and towns—Government, public institutions, education, etc. | 133 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE COLONY OF VICTORIA. | |

| PAGE | |

| Origin, geographical limits, and area—Physical features—Climate, natural history, and geology—Colonisation, population, etc.—Productions, trade, shipping, etc.—Roads, railways, and telegraphs—Political and civil divisions—Cities and towns—Government, religion, public institutions, education, etc. | 165 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

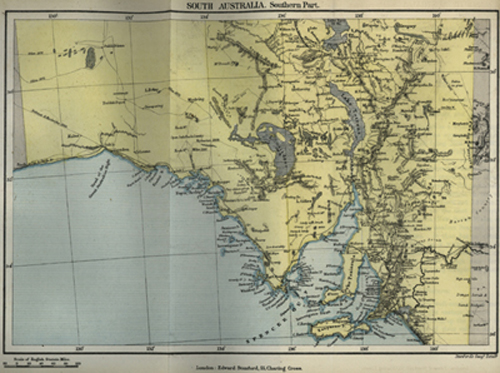

| THE COLONY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA. | |

| Origin, geographical limits, and area—Physical features—Climate, natural history, and geology—Colonisation, population, etc.—Productions, trade, shipping, etc.—Roads, railways, and telegraphs—Political divisions, cities, and towns—Government, public institutions, education, etc.—The northern territory | 192 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE COLONY OF WEST AUSTRALIA. | |

| Origin, geographical limits, and area—Physical features—Climate, natural history, and geology—Colonisation, population, etc.—Productions, trade, etc.—Communications—Political divisions, cities, and towns—Government, education, etc. | 208 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE COLONY OF QUEENSLAND. | |

| Origin, geographical limits, and area—Physical features—Climate, natural history, and geology—Population—Productions and trade—Political divisions—Cities and towns—Government, religion, education, etc. | 218 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE COLONY OF TASMANIA. | |

| Origin, position, area—Physical features—Rivers—Lakes—Climate, natural history, and geology—Colonisation, population, etc.— |

| Aborigines—Productions and trade—Roads, railways, and telegraphs—Political divisions, cities, and towns—Government, religion, education, etc. | 239 |

| THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| GEOGRAPHICAL AND ETHNICAL SURVEY OF THE ARCHIPELAGO. | |

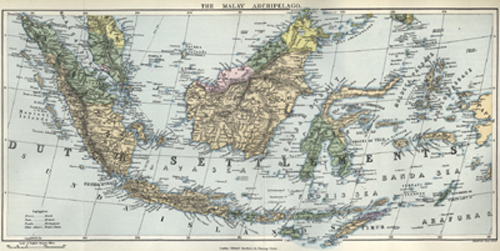

| Geographical outline—Physical features, volcanoes—The Malay race and language—Savage and semi-civilised Malays | 255 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. | |

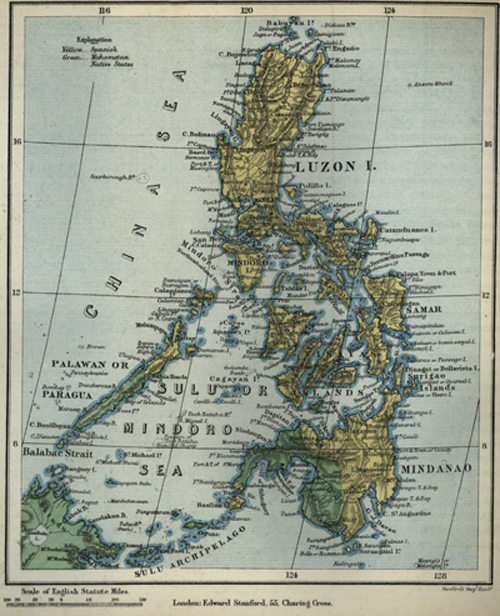

| Geographical outline—Scenery—Natural history—Native inhabitants—Negritos—European conquest of the Philippines—Government, population—Trade and commerce—Luzon—Mindoro—Panay—Negros—Cebu—Samar—Leyte—Masbate, Bohol—Palawan—Mindanao—The Sooloo Islands | 267 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE DUTCH EAST INDIES. | |

| Extent and importance—Dutch policy, and its effects on the native populations—System of government of Netherlands India | 299 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| JAVA. | |

| Position, form, and area—Mountains, volcanoes, earthquakes—rivers, valleys, hot springs, etc.—Climate—Natural history—Inhabitants—Language, government, antiquities—Dutch conquest of Java, population, etc.—Products and revenue—Cities, towns, and villages—Communications, commerce, etc. | 302 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| SUMATRA. | |

| PAGE | |

| Position and area—Mountains, volcanoes, plains—Lakes and rivers—Natural history—Races of man—Achin—Palembang—Islands belonging to Sumatra—The Dutch possessions and the chief towns | 329 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| BORNEO. | |

| Dimensions form, and ontline—Mountains and rivers—Geology and natural history—Native races—European settlements in Borneo—The English settlements at Sarawak and Labuan—Present condition of Sarawak—Native population—Government—Military force—Exports and imports, revenue, etc.—Religion and education—General remarks on the character and influence of the Sarawak Government—Labuan—Chief towns, islands, etc. | 347 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| CELEBES. | |

| Position, extent, and outline—Physical features—Natural history—Native races—Dutch possessions and native kingdoms of Celebes—Macassar—Native States—Menado—Islands belonging to Celebes | 379 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| THE MOLUCCAS. | |

| Position, size, etc.—Geology and natural history—Inhabitants—Ternate and the Gilolo group—Amboyna and the Ceram group—Bouru—Amboyna—Banda—Islands east of Ceram—The Ké Islands | 396 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE TIMOR GROUP. | |

| Physical description—Natural history—Races of mankind—Bali—Lombok—Sumbawa—Flores and Sandalwood Island—Timor—Islands east of Timor | 417 |

| MELANESIA. | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| NEW GUINEA AND THE PAPUANS. | |

| PAGE | |

| Position, dimensions, etc.—Physical features—Early history and recent exploration—Geology and natural history—Animal life—The Papuan race—Local divisions of New Guinea—Missionary stations in New Guinea—Papuan Islands | 434 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| OTHER ISLANDS OF MELANESIA. | |

| The Admiralty Islands—The New Britain group—The Solomon Islands—The New Hebrides and Santa Cruz groups—New Caledonia and the Loyalty Islands—The Fiji Islands | 465 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

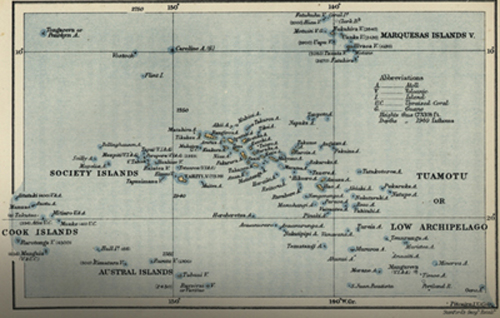

| POLYNESIA. | |

| Extent and component groups—The Polynesian or Mahori race—The Tonga or Friendly Islands—The Samoa or Navigator's Islands—Savage Island—The Union and Ellice Islands—The Hervey Islands, or Cook's Archipelago—The Society Islands—The Austral Isles and Low Archipelago—Pitcairn and Easter Islands—The Marquesas Islands—Manihiki, America, and Phœnix groups—The Sandwich Islands | 492 |

| MIKRONESIA. | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| MIKRONESIA. | |

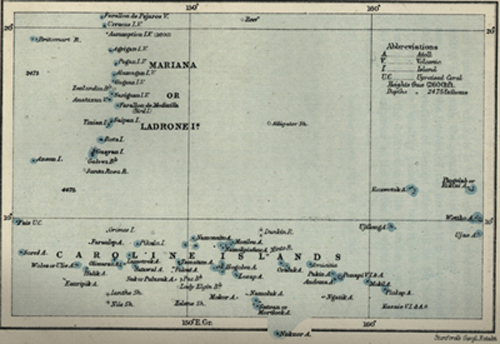

| Extent and component groups—The Marshall Archipelago—The Gilbert or Kingsmill Islands—The Caroline Archipelago—Ponapé and its ruins—The Pelew Islands—The Mariannes or Ladrone Islands | 533 |

| NEW ZEALAND. | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| PHYSICAL HISTORY OF THE NEW ZEALAND GROUP. | |

| PAGE | |

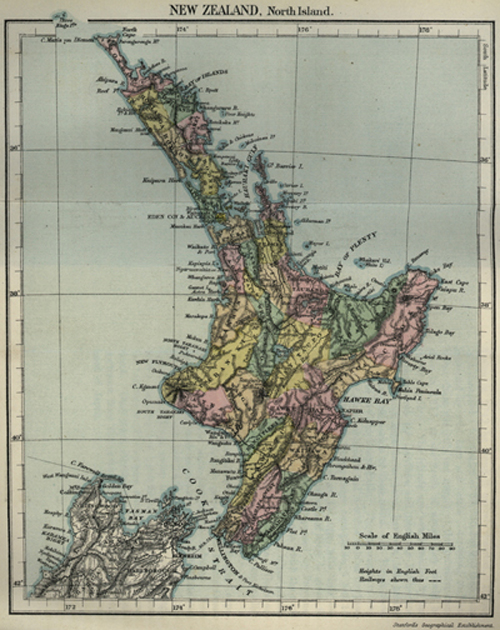

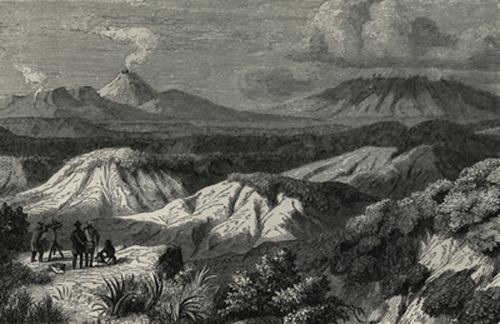

| Position, extent, islands, etc.—Physical features and scenery—Lakes, hot springs, and glaciers—Climate—Geology—Natural history—Past history of New Zealand—The Maories and the aborigines of New Zealand—Other islands of the New Zealand group | 545 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| THE COLONY OF NEW ZEALAND. | |

| Colonisation and population—Agricultural and industrial pursuits—Railroads and communications—Political divisions—Provincial district of Auckland—District of Taranaki—District of Hawkes' Bay—District of Wellington—District of Nelson—District of Marlborough—District of Canterbury—District of Westland—District of Otago—Government, education, religion, etc. | 577 |

| APPENDIX BY A. H. KEANE. | |

| PHILOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY OF THE INTEROCEANIC RACES. | |

| Area—Dark and brown types—Nomenclature—Interoceanic—Negrito—Papûa—Alfuro—Malayo-Polynesian—Indo-Pacific—Micronesian—Mahori—Comparative table of physical characteristics—General scheme of Interoceanic races and languages: I. The Austral Races; II. The Negrito Races; III. The Papûan Races; IV. The Mahori Race; V. The Mikronesian Races; VI. The Malayan Races | 593 |

| COMPARATIVE TABLE of INTEROCEANIC NUMERALS | 626 |

| ALPHABETICAL LIST of INTEROCEANIC RACES and LANGUAGES | 627 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| New Zealand Chief | Frontispiece. |

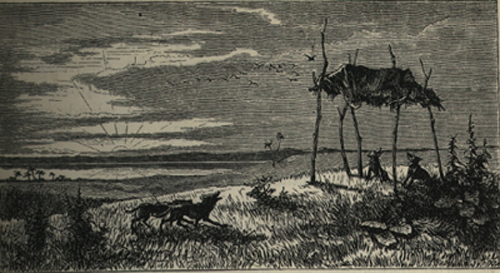

| A Burial in the Australian Steppes | Page 1 |

| The Blue Mountains | „ 16 |

| The Murray | „ 24 |

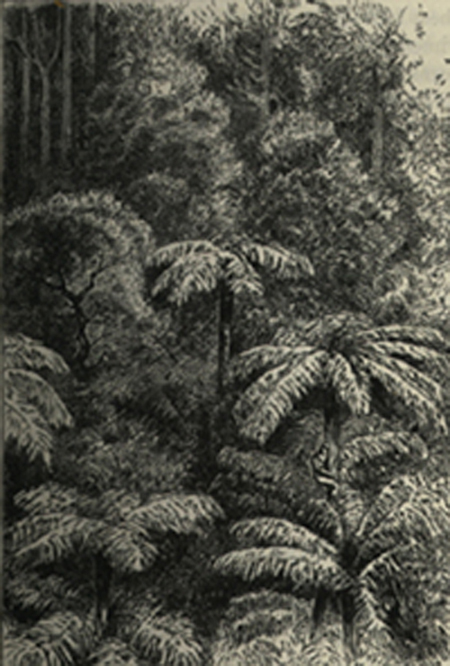

| Australian Forest | „ 37 |

| Kangaroo | „ 54 |

| Emu | To face page 60 |

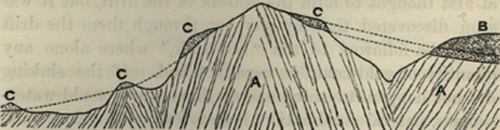

| Geological Section: "Oldest" Drifts | Page 72 |

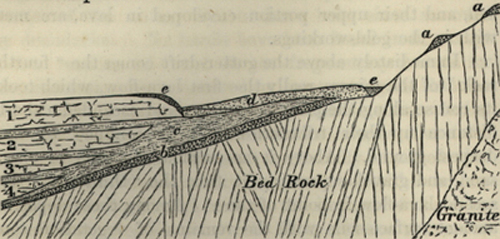

| Do. Drifts and Lava-flows | „ 74 |

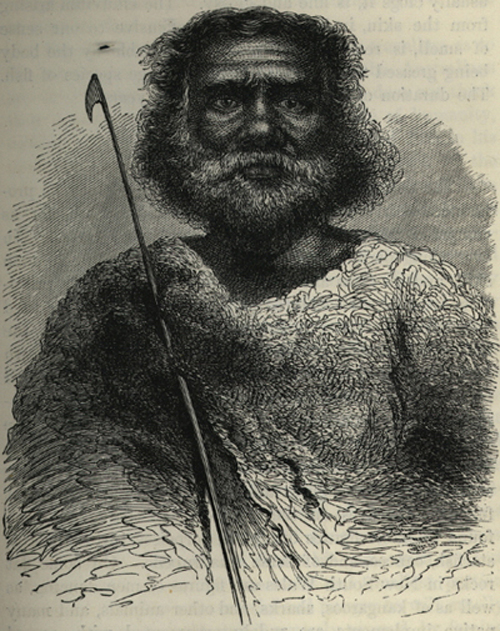

| Native Australian | „ 87 |

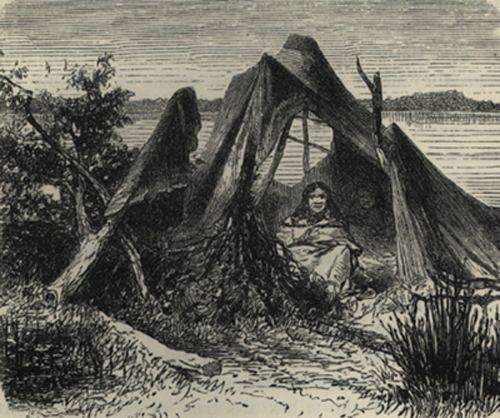

| Native Australian Hut | „ 92 |

| Cooper's Creek | To face page 120 |

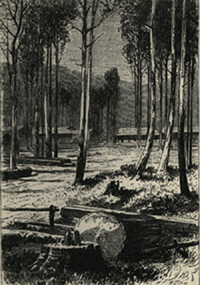

| Settlement on a Gold-field | Page 130 |

| Entrance to Port Jackson | To face page 137 |

| Sydney | Page 155 |

| Collins Street, Melbourne | „ 183 |

| A Piratical Fleet | To face page 297 |

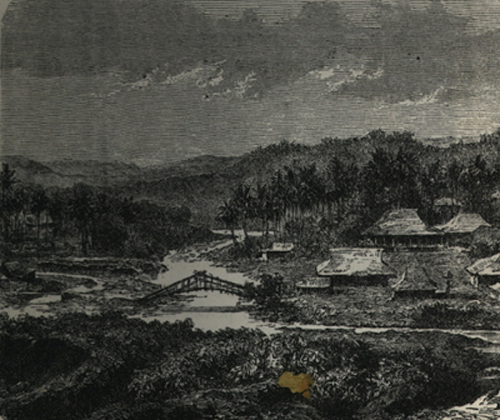

| Javanese Landscape | Page 303 |

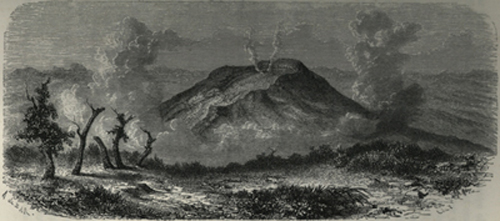

| Volcano in Java | To face page 304 |

| A Native House, Java | Page 323 |

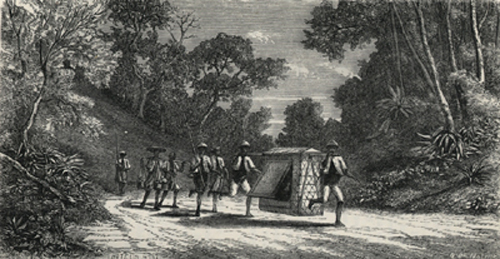

| Inland Travelling in Java | To face page 327 |

| Palace of a Sumatra Prince | Page 336 |

| A Dyak Warrior | „ 356 |

| A Dyak Dancer | „ 357 |

| Exterior of a Dyak Village | „ 359 |

| Interior of a Dyak Village | „ 360 |

| Dyak Bamboo Bridge | To face page 361 |

| Babirusa | Page 382 |

| Scene in the Moluccas | To face page 396 |

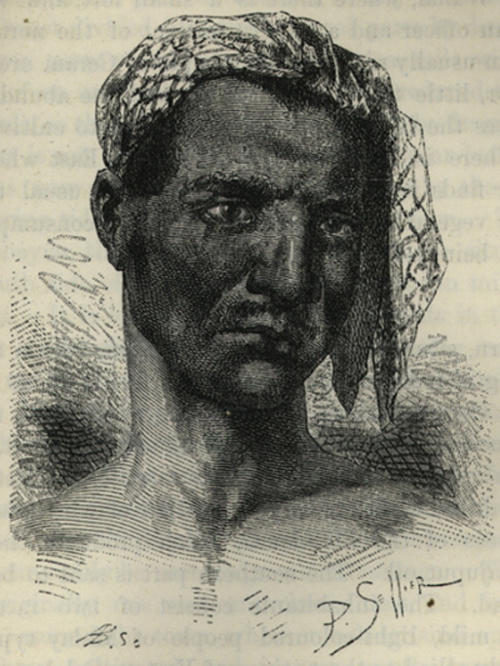

| Native of Ceram | Page 407 |

| Banda Volcano | „ 412 |

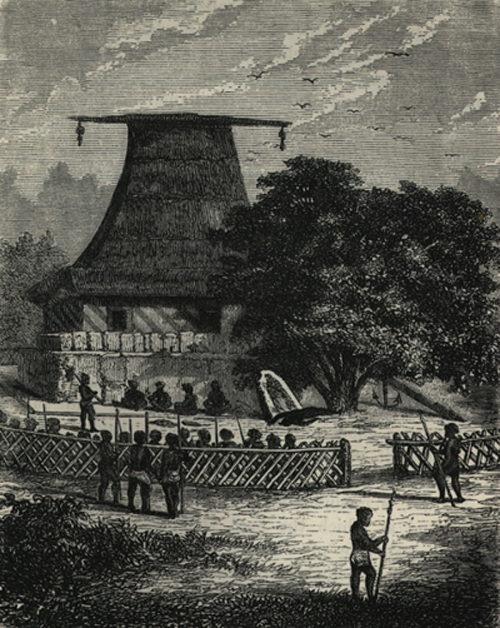

| The Royal Palace, Bali | „ 421 |

| Village of Dorey | To face page 440 |

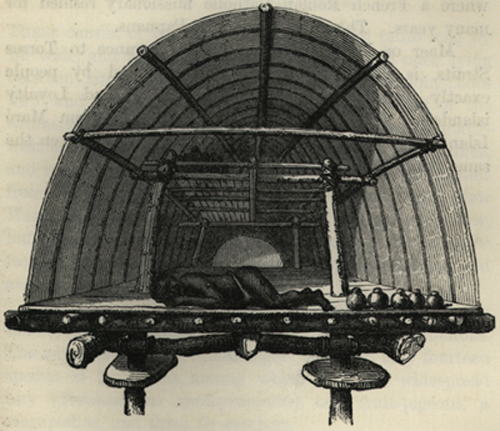

| Inside of Hut, Louisiade Archipelago | Page 463 |

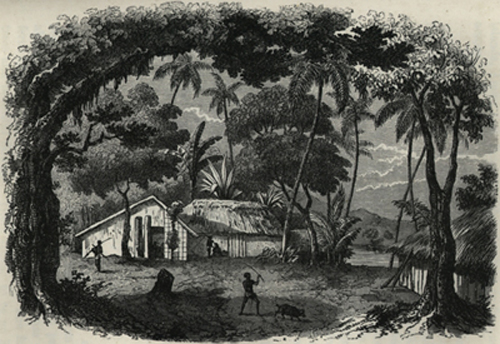

| Village in Vanikoro | To face page 474 |

| Chief of Vanikoro | Page 476 |

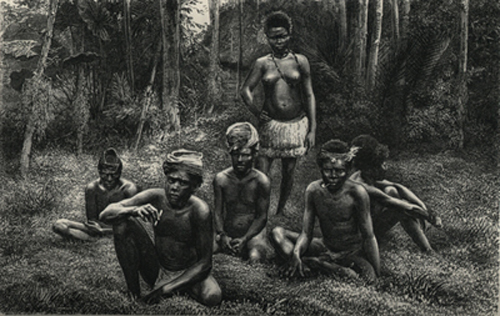

| Natives of New Caledonia | To face page 481 |

| New Caledonian Flute-player | Page 482 |

| Native of Fiji | „ 486 |

| Fiji Temple | „ 489 |

| Ancient Tomb, Tahiti | „ 496 |

| Atoll in the Samoa Group | „ 501 |

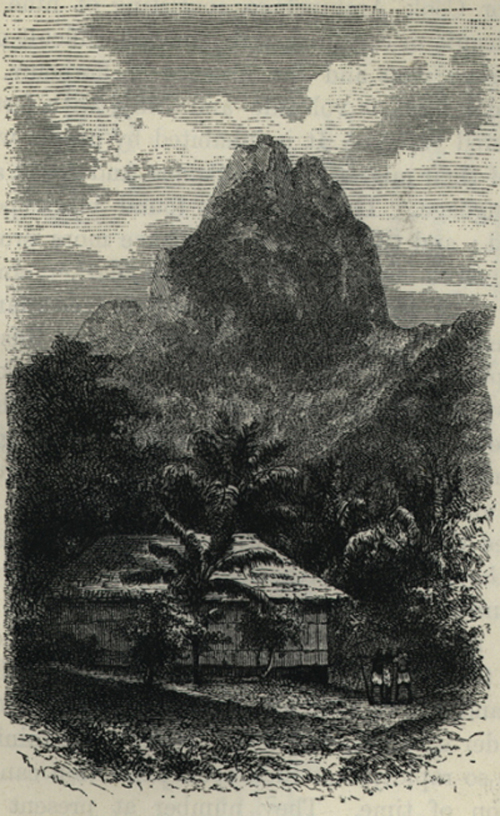

| Peak of Moorea | „ 508 |

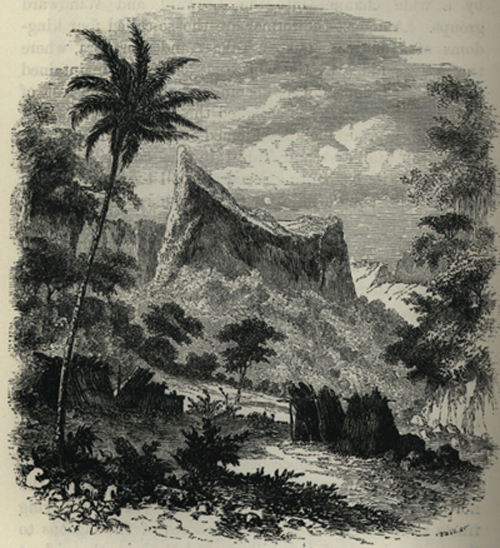

| View on the Shores of Tahiti | To face page 509 |

| Mountains of Tahiti | Page 510 |

| Natives of Society Islands fishing | „ 513 |

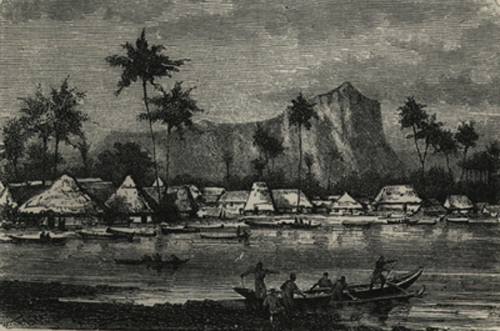

| Bay of Karakora, where Captain Cook was killed | To fact page 525 |

| Kilauea Volcano | Page 527 |

| Village in Hawaii | „ 529 |

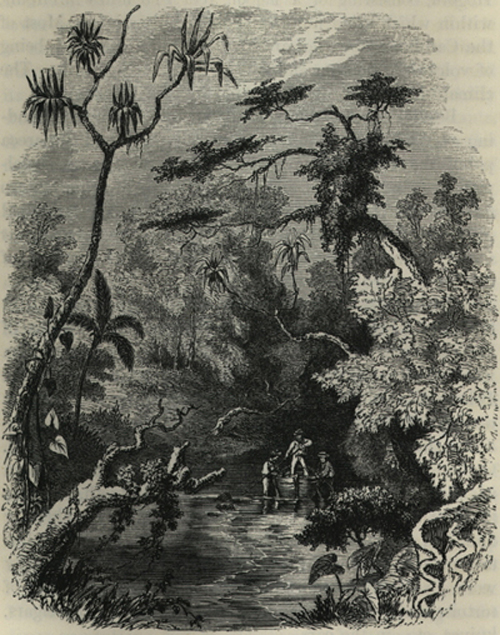

| Creek in the Caroline Islands | „ 537 |

| Tangariro and Ruapehu | To face page 546 |

| Geysers near the River Waikato | Page 549 |

| Glaciers of Mount Cook | To face page 552 |

| Maori Type | Page 565 |

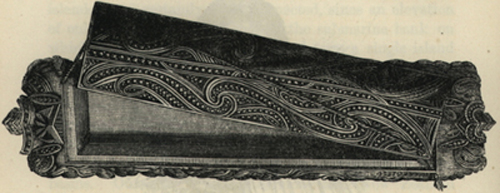

| Carved New Zealand Chest | „ 566 |

| War Club of New Zealand | „ 568 |

LIST OF MAPS.

| Index Map to Chapters and Sections | To face Contents. |

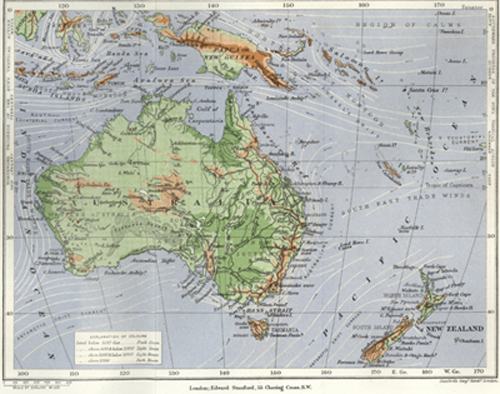

| General Map of Australasia, with depths of the Sea | „ page 1 |

| Physical Map of Australasia | „ „ 13 |

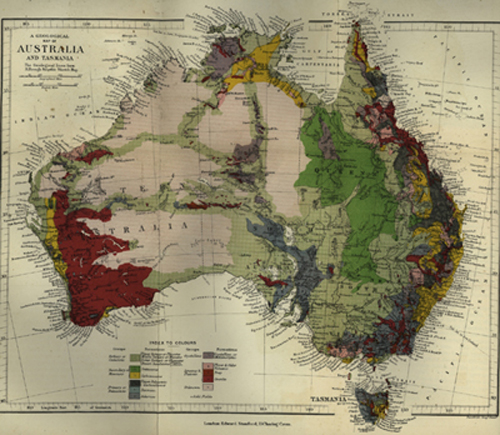

| Geological Map of Australia | „ „ 65 |

| General Map of Australia | „ „ 107 |

| Map of New South Wales | „ „ 133 |

| „ Victoria | „ „ 165 |

| „ South Australia | „ „ 193 |

| „ West Australia | „ „ 209 |

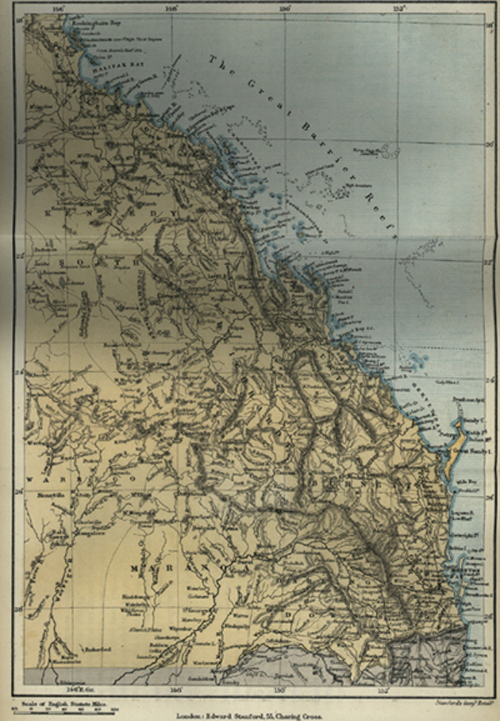

| „ Queensland | „ „ 219 |

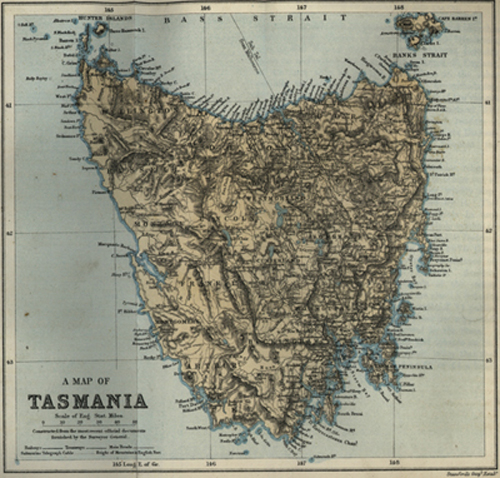

| „ Tasmania | „ „ 239 |

| „ Philippine Islands | „ „ 267 |

| „ Malay Archipelago | „ „ 299 |

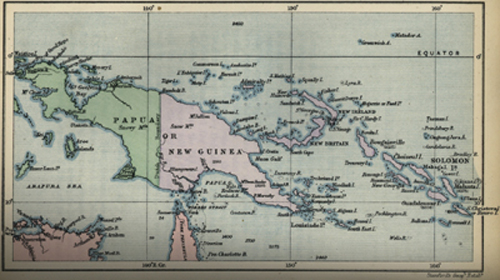

| „ New Guinea and Solomon Islands | „ „ 435 |

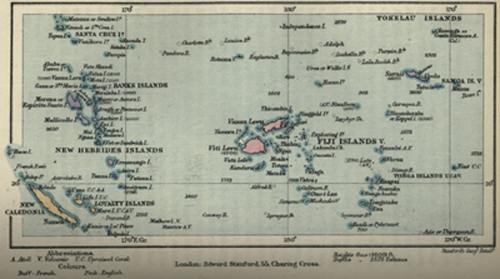

| „ New Caledonia and Samoa Islands | „ „ 473 |

| „ Society Islands and Marquesas | „ „ 507 |

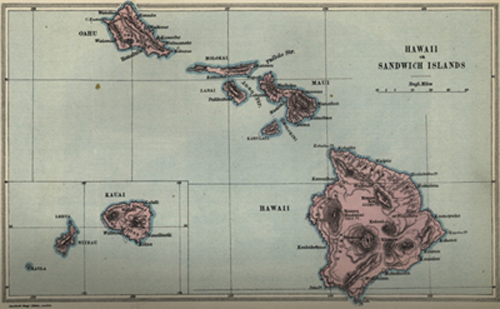

| „ Sandwich Islands | „ „ 525 |

| „ Caroline and Ladrone Islands | „ „ 533 |

| „ New Zealand (North Island) | „ „ 545 |

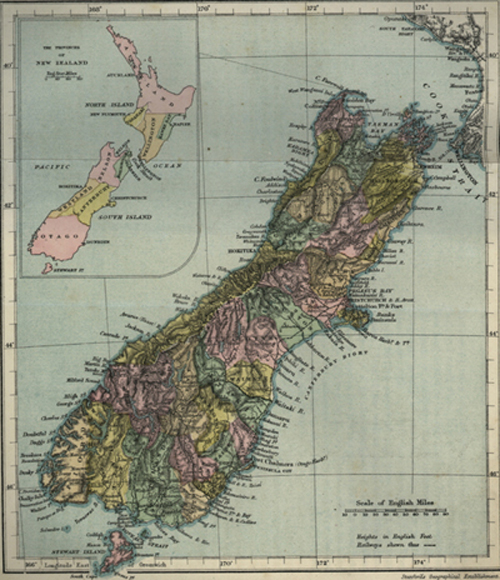

| „ Do. (South Island) | „ „ 577 |

A CHART OF AUSTRALASIA SHEWING THE DEPTH OF THE SEA.

A BURIAL IN THE AUSTRALIAN STEPPES.

AUSTRALASIA.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION.

1. Definition and Nomenclature.

THE present volume will be devoted to a description of the great insular land—Australia, and of all the archipelagoes and island-groups which extend almost uninterruptedly from the south-eastern extremity of Asia to more than half-way across the Pacific Ocean. It thus includes all the islands of the Malay Archipelago, the greater portion of which are usually joined to Asia, as well as the various groups of islands in the Pacific which have received special names—as Micronesia, Polynesia, etc. The term Australasia has been used in very different senses. In the original German edition of this work it included the whole area as above defined, except the

B

Malay Islands west of New Guinea, which were united with Asia. In the last edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (now publishing) it is held to comprise only Australia and New Zealand, with the large islands as far as New Guinea and the New Hebrides. Oceania is the word often used by continental geographers to describe the great world of islands we are now entering upon; but, as defining one of the six great divisions of the globe, Australasia harmonises better with the names of the other divisions, and at the same time serves to recall its essential characteristics—firstly, that it is geographically a southern extension of Asia; and, secondly, that the great island-continent of Australia forms its central and most important feature.

2. Extent and Distribution of Lands and Islands.

That portion of the equator stretching from the southern extremity of the Indo-Chinese peninsula at Singapore to the opposite shores of America near Guayaquil, occupies almost exactly 180 degrees of longitude, or half the circumference of the globe; and throughout almost the whole of this vast distance it traverses the blue waters of the Pacific Ocean. This boundless watery domain, which extends northwards to Behring Straits and southward to the Antarctic barrier of ice, is studded with many island groups, which are, however, very irregularly distributed over its surface. The more northerly section, lying between Japan and California and between the Aleutian and Hawaiian Archipelagoes, is relieved by nothing but a few solitary reefs and rocks at enormously distant intervals. Between the tropics, islets, reefs, and groups of coral formation abound; and towards the southern limits of this belt larger islands appear, which increase in size as we go westward, till we reach New

Guinea and the other large islands of the Malay Archipelago. To the eastward, the Pacific is almost entirely destitute of islands, till a few occur near the American coast; so that an unbroken belt of ocean, nearly two thousand miles wide, forms a mighty barrier between Australasia and the continents of North and South America. A little to the south of the tropic of Capricorn, islands almost wholly cease in the Central Pacific; but going westward we meet with the important New Zealand group, and farther on the island-continent of Australia, with its satellite Tasmania, closely connected with New Guinea and the other Malay Islands. It thus appears that all the greater land masses of Australasia form an obvious southern and south-eastern extension of the great Asiatic continent, while beyond these the islands rapidly diminish in size and frequency, till in the far east we reach a vast expanse of unbroken ocean.

Estimated by its actual land area, this division of the globe is only a little larger than Europe; but if we take account of the surface it occupies upon the globe, and the position of its extreme points, it at once rises to the first rank, surpassing even the vast extent of the Asiatic continent. From the north-western extremity of Sumatra, in 95° east longitude, to the Marquesas in 138° west, is a distance of 127°, or more than one-third the circumference of the globe, and about a thousand miles longer than the greatest extent of Europe and Asia from Lisbon to Singapore. In a north and south direction it is less extensive; yet from the Sandwich Islands in 22° north, to the south island of New Zealand in 47° south latitude, is a meridian distance of 69 degrees, or as much as the width of the great northern continent from the North Cape to Ceylon. Its extreme limits are indeed much greater than above indicated, for in the West Pacific the islands extend to beyond 30° north latitude; in the east

we have Easter Island and Sala-y-Gomez full 30 degrees beyond the Marquesas; while in the south the Macquarie Islands are about 600 miles south of New Zealand.

3. Geographical and Physical Features.

Within the limits above described are some of the most interesting countries of the world. Beginning at the west, we have the Malay Archipelago, comprising the largest islands on the globe (if we exclude Australia), and unsurpassed for the luxuriance of its vegetation as well as for the variety and beauty of its forms of animal life. Farther to the east we have the countless islands of the Pacific, remarkable for their numbers and their beauty, and interesting from their association with the names of many of our greatest navigators. To the south we have Australia, a land as unique in its physical features as it is in its strange forms of vegetable and animal life. Still farther in the Southern Ocean lies New Zealand, almost the antipodes of Britain, but possessing a milder climate and a more varied surface.

Being thus almost wholly comprised between the northern tropic and the 40th degree of south latitude, this division of the globe possesses as tropical a character as Africa, while, owing to its being so completely oceanic, and extending over so vast an area, it presents diversities of physical features and of organic life hardly to be found in any of the other divisions of the globe, except, perhaps, Asia. The most striking contrasts of geological structure are exhibited by the coral islands of the Pacific, the active volcanoes of the Malay Islands, and the extremely ancient rocks of New Zealand and Tasmania. The most opposite aspects of vegetation are presented by the luxuriant forests of Borneo or New Guinea and the waterless plains of Central Australia. In the Sunda Islands we have an

abundance of all the higher and larger forms of mammalia; while farther to the east, in Australia and the Pacific Islands, the absence of all the higher mammalia is so marked as to distinguish these countries from every other part of the world. Where the land surface is so completely broken up into islands we cannot expect to find any of the more prominent geographical features which characterise large continents. There are no great lakes, rivers, or mountain ranges. The only land-area capable of supporting a great river is exceptionally arid, yet the Murray of Eastern Australia will rank with the largest European rivers, its basin having an area about equal to that of the Dnieper. Mountains are numerous, and are much higher in the islands than in Australia itself. In such remote localities as Sumatra, Borneo, the Sandwich Islands, and New Zealand, there are mountains which just fall short of 14,000 feet. In New Guinea they probably exceed this altitude, if, as reported, the central range situated close to the equator is snow-covered; while in Australia the most elevated point is little more than half as high.

4. Ocean Depths.

The land and water of the earth's surface is so unequally distributed that it is possible to divide the globe into two equal parts, in one of which (the land hemisphere) land and water shall be almost exactly equal, while in the other (the water hemisphere) there shall be almost eight times as much water as land. The centre of the former is in St. George's Channel, about midway between Pembroke and Wexford; and the centre of the latter will be about 600 miles S.S.E. of New Zealand. Australasia is therefore situated wholly within the water hemisphere, and many of its islands are surrounded by an ocean which is not only the most extensive but the deepest on the globe.

The Pacific Ocean is deepest north of the equator, where soundings of from 15,000 to 18,000 feet have been obtained over an extensive area; and it is a remarkable fact that the depth increases as we approach the Asiatic continent. Between the Philippines and the Marianne Islands a depth of nearly 27,000 feet has been found; close to Japan, 23,400 feet; and just south of the Kurile Islands, the enormous depth of 27,930 feet. In the South Pacific the depths, as far as yet ascertained, vary between 10,000 and 17,000 feet; but here, too, the deepest soundings are near the larger land masses, close to the New Hebrides (16,900 feet), between Sydney and New Zealand (15,600 feet), and a little south-east of New Guinea (14,700 feet). A comparatively shallow sea extends round the coasts of Australia, which gradually deepens, till at a distance of from 300 to 500 miles on the east, south, and west, the oceanic depth of 15,000 feet is attained. The sea connecting Australia with New Guinea and the Moluccas is rather shallow, with intervening basins of immense depth. In the Banda sea there is a basin at least 12,000 feet deep; while in the Celebes and Sooloo seas are similar basins of over 15,000 feet; and in the China sea, west of Luzon, one of 12,600 feet. Farther westward the sea shallows abruptly, so that Borneo, Java, and Sumatra are connected with each other and with the Malay and Siamese peninsulas by a submarine bank rarely exceeding 200 or 300 feet deep.

5. Races of Mankind.

Australasia surpasses most of the great continental divisions of the globe in the variety of human races which inhabit it, and in the interesting problems which they present to the anthropologist. We may reckon at least three, or, as some think, five or even six distinct types of

mankind in this area. First, we have the true Malays, who inhabit all the western portion of the Malay Archipelago from Sumatra to the Moluccas; next we have the Papuans, whose head-quarters are New Guinea, but who range to Timor and Flores on the west, and to the Fiji Islands on the east. The Australians form a third race, universally admitted to be distinct from the other two. Then come the Polynesians, inhabiting all the Central Pacific from the Sandwich Islands to New Zealand. These are usually classed with the Malays on account of some similarity of language and colour, and are therefore erroneously called Malayo-Polynesians. But they present many and important differences, both physical and mental, from all Malays, and the best authorities now believe them to be an altogether distinct race. The now extinct Tasmanians are also of disputed origin, some writers classing them with the Papuans of New Guinea, while others refer them to the same race as the indigenes of Australia. Besides these, we have the dwarfish race called Negritos, who inhabit some parts of the Philippines, and are allied to the Semangs of the Malay peninsula, and perhaps to the Andaman Islanders.

The Australian natives occupy unquestionably the very lowest social position in the human family. The Papuans inhabit the division of Australasia collectively known as Melanesia; and the distinction that has been drawn between the Papuans proper and a special Melanesian type seems needless and fanciful. On the other hand, the Papuan must not be identified with the Australian, the results of extensive philological researches being entirely opposed to such a conclusion. The Australian idioms are characterised exclusively by suffix formations, whereas the Papuan tongues show a preference rather for prefixes,—a fundamental difference altogether excluding any relationship between the two linguistic systems.

The black, woolly-haired, Papuan type is found not only in the Melanesian group, but traces of apparently the same dark race may be detected throughout the whole of Polynesia and Micronesia. Everywhere in Polynesia we meet with individuals, who, in their dark and even black complexions and curly or woolly hair, closely resemble the Papuans.

The light type is, on the other hand, represented by the Malays and Polynesians, who in some places, such as Samoa and the Marquesas, are in no respects inferior to the average European, either in their complexion, physical beauty, or nobility of expression. Nevertheless, these higher tribes are all disappearing under the fatal contact of our much-vaunted civilisation; and nowhere is the steady process of extinction developing on such a grand scale as amongst the South Sea Islanders.

Australasia also affords us an unusual number of interesting examples of immigration and colonisation by higher races. The Malay Archipelago was the scene of the earliest European settlements in eastern Asia, the Portuguese and Spaniards taking the lead, to be quickly followed by the Dutch and English. Each of these governments has colonies in some of the Malay Islands, and the French have more recently established themselves in New Caledonia and Tahiti. Australia and New Zealand are examples of highly successful colonisation, and their recent material progress has been as striking as the contemporaneous development of the Western United States. Here, too, we have examples of the overflow of the vast population of China. In all the cities, towns, and villages of the archipelago, from Malacca on the west to the Aru Islands on the east, the Chinese form an important portion, and often indeed the bulk of the population; and since the gold discoveries in Australia they have extended their emigration into many parts of that exten-

sive country. In Java, and less distinctly in Sumatra and Borneo, there are numerous remains showing an ancient Brahminical occupation, previous to the later Mahometan conquest of the country. And, lastly, throughout the whole archipelago and in Polynesia, we find traces of a recent extension of the Malays and their language at the expense of less civilised tribes.

6. Zoology and Botany.

The larger part of Australasia forms one of the great zoological regions of the earth—the Australian—characterised by possessing a number of very peculiar forms of life, as well as by the absence of many which are common in almost every other part of the globe. Its mammalia almost all belong to the marsupial type, which is only represented elsewhere by a few opossums in America. Honey-suckers, paradise-birds, lyre-birds, and cassowaries are confined to it, as well as numbers of very remarkable parrots, pigeons, and kingfishers; while such widespread and familiar types as vultures, pheasants, and woodpeckers are altogether wanting. The snakes and lizards are numerous and peculiar; while insects and land-shells abound, and present a number of the most interesting and beautiful species. The western half of the Malay Archipelago belongs zoologically to tropical Asia, and possesses almost every form of animal life found in the Siamese and Birmese countries, but for the most part of peculiar species.

Plants are equally interesting. The Malayan flora is a special development of that which prevails from the Himalayas to the Malay Peninsula and South China. Farther east this flora intermingles with that of Australia and Polynesia. The Australian flora is highly peculiar and very rich in species; while that of New Zealand is

poor but very isolated. A sketch of the general character of each of these floras will be given farther on.

7. Geological Relations and Past History.

The western half of the Malay Archipelago, as far as Java, Borneo, and perhaps the Philippines, has undoubtedly, at a comparatively recent period, formed a southeastern extension of the Asiatic continent. This is indicated by the exceedingly shallow sea which connects these islands with the mainland, but still more clearly by the essential unity of their animal and vegetable productions. Tigers, elephants, rhinoceroses, tapirs, and wild cattle, are found in Borneo, and many of them even in Java; and the mass of the vertebrata of these islands are either identical with those of the continent, or closely related to them. But as we go farther east to the Moluccas, New Guinea, and Australia, we have to pass over seas of enormous depth, and there find ourselves among a set of animals for the most part totally unlike those of the Asiatic continent, or any other part of the globe. Yet these have certain resemblances to the fauna of Europe during the Secondary period of geology, and it is very generally believed that the countries they now inhabit have been almost completely isolated since the time of the Oolitic formation.

New Guinea, the Moluccas, Celebes, and the island chain as far as Lombok, or some pre-existing lands from which these have been formed, were in all probability still attached to the Australian mainland for some time subsequent to its severance from Asia. Cape York, at the northern extremity of the Carpentarian peninsula, is continued by a chain of high rocky islets all the way to New Guinea, while the depth of Torres Strait itself, flowing between New Guinea and Australia, nowhere exceeds nine

fathoms. On the other hand, the Louisiade Archipelago, north-east of Australia, is nothing more than a submerged portion of the south-eastern extremity of New Guinea. Tasmania must similarly be regarded as the true southern point of Australia, as the intervening Bass's Strait is shallow, and this island was within a comparatively recent geological epoch undoubtedly connected with the mainland.

Hence, in Peschel's opinion, Australia was formerly far more extensive than at present. It has clearly been encroached upon along its eastern seaboard, for here stretches the dreaded Great Barrier Reef, whose coral walls sink to considerable depths below the surface, and which still shadows forth the former limits of the coast line in this direction. On this same eastern seaboard, though much more removed from the mainland, we meet some larger islands which (though perhaps before the Tertiary epoch) may well have formed part of the Australian continent. Conspicuous amongst them is the non-volcanie island of New Caledonia, which is at present slowly subsiding.

Australia must, in fact, be altogether regarded as a continent of the Secondary or early Tertiary period now gradually disappearing, and this phenomenon of subsidence is displayed even on a still vaster scale throughout the whole extent of the South Pacific Ocean. All the so-called "atolls," or true coral, islands, have been built up on a foundation of sunken land, and the bottom of the ocean is itself even now subsiding more and more. Of the former lands now submerged beneath the ocean waves, nothing has survived except the highest mountain crests still represented by the countless South Sea Islands.

8. Geographical Divisions.

For the purposes of this work we shall consider Aus-

tralasia as consisting of six parts, each of which has a distinctive name and is usually treated as forming a geographical unit, although some of them are really heterogeneous, and should be differently subdivided to accord with their zoological relations and geological history. These divisions are—(1.) Australia, including Tasmania; (2.) Malaysia, including the islands of the Malay Archipelago from Sumatra to the Philippines and Moluccas, and forming the home of the true Malay race; (3.) Melanesia, including the chief islands inhabited by the black and woolly-haired race from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands; (4.) Polynesia, including all the larger islands of the Central Pacific from the Sandwich Islands southward; (5.) Micronesia, comprising the small islands of the North Pacific; and (6.) the New Zealand group.

These will be further subdivided as occasion requires, and will be taken in the order above indicated.

PHYSICAL MAP OF AUSTRALASIA

London; Edward Stamford, 55 Charing Cross, S.W.

AUSTRALIA.

CHAPTER II.

THE PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE OF AUSTRALIA.

1. Dimensions, Form, and Outline.

UNTIL recently the Australian continent, especially in its western half, was one of the least known regions of the globe. But for some years past the exploration of the country has made such rapid strides, that we are already in a position to form a clear idea of its general character, while, even regarding its more special features very little will soon remain to be done.

With a total area of 2,983,200 square miles—that is, rather less than Europe—the Australian continent forms a somewhat unshapely mass of land, with little-varied outlines, and a monotonous seaboard, washed on the west by the Indian, and on the east by the Pacific Ocean. In the North it is separated from New Guinea by Torres Strait, 90 miles in breadth; and in the south, from Tasmania by the much-frequented yet dangerous Bass's Strait. Parallel with, and about 60 miles distant from the east coast, stretches the Great Barrier Reef, which, throughout its entire length of 1200 miles, presents only a single safe opening for ships; and which reaches northwards almost to the extremity of York Peninsula. This peninsula, which is the most distinctive geographical feature of the Australian continent, forms, with the more westerly, but

far less boldly developed peninsula of Arnhem Land, the great northern bight known as the Gulf of Carpentaria. Corresponding with this inlet is the Great Australian Bight on the south coast, but neither of them materially affects the general character of this continent as a compact and but slightly varied mass of land. The west coast is, on the whole, richer in bights and inlets, and also possesses several good harbours. In the south, besides the already-mentioned Great Bight, nothing occurs to vary the monotony of the coast line except Spencer and Vincent Gulfs, with the neighbouring Kangaroo Island, and the narrow York Peninsula, not to be confounded with that of like name in the north.

2. General Contour of the Country.

The conformation of the land is no less simple than the outlines of the coast. It rises generally from south to north, and from west to east. Mountains of considerable size are found in the east alone, where they stretch in several ranges parallel with the coast from Bass's Strait northwards to the low-lying York Peninsula. But even in Western Australia we meet with elevated uplands sinking abruptly in some directions. On the other hand, the assumption that Australia forms a vast table-land, with elevated borders, and sloping towards the interior, where its lowest level is that of Lake Eyre (70 feet above the sea), must be taken with considerable qualifications. It is, however, so far true in a general way, that lowlands form the prevailing feature of the inland country.

The Australian highlands themselves form no connected whole, being everywhere intersected by depressions of all sorts, to such an extent, that a mere rising of the sea-level of no more than 500 feet would probably convert the whole continent into a group of numerous

islands, varying in size and elevation. These highlands generally present the appearance of hilly upland plains, and are mostly covered with park-like and grassy forests, but without the undergrowth, here called "scrub," which is elsewhere peculiar to Australia. Here the river valleys are generally fertile, and more especially adapted for agriculture. The cultivable land, however, is everywhere distributed somewhat disconnectedly, and in the form of isolated oases over the country.

The gorges through which the streams mostly make their way from the hills, are usually deep and difficult of access, but are nevertheless distinguished, especially in the south, by a rich and almost tropical vegetation. Above the upland plains there often rise rocky mountains, in most cases forming connected chains, in many places presenting steep and rugged escarpments, elsewhere sloping gently and gradually down to the plains. Nor are terrace-like formations altogether wanting, though these are of limited extent and imperfectly developed.

A further peculiarity of the Australian highlands is their distribution mainly along the coast, round about the interior, where no extensive mountain ranges have hitherto been discovered. Of distinct coast ranges six have already been determined, the most important of which is that of Victoria and New South Wales, in the south-east corner of the continent.

3. Mountains and Table-lands.

The Victoria highlands form a hilly, upland, and mostly fertile plain, above which rise two distinct ranges, running north and south, the Grampians in the west, and the Pyrenees and Dividing Range to the east; while the southern slopes are distinguished by a series of low volcanic hills, with craters only recently extinct. Farther

THE BLUE MOUNTAINS.

east these highlands are separated by a broad depression from the chain of the Australian Alps, or Warragong Mountains, culminating in Mount Kosciusko (7308 feet), just within the borders of New South Wales, and the highest elevation of the continent. Separated from them by upland valleys are the wooded but infertile Blue Mountains and the Liverpool Range, running exceptionally east and west, and along whose northern slopes stretch the rich and lovely Liverpool Plains. East and west of them extend other more elevated plains, reaching far north, and forming the fine pasture-lands of New England, which stretch almost to the northern limits of the highlands. These consist of the Dividing Range, skirting the valley of the coast river Brisbane on the west, and sinking northwards down to the valley of the Burnett. On the western slopes of the Dividing Range lie the rich

and pleasant grassy plains of the Canning and Darling Downs, watered by the river Condamine, flowing inland.

North of the two last-named rivers begin the Queensland highlands, stretching in a comparatively narrow chain in a north-westerly direction as far as the 17° S. lat., and divided into two formations by a depression in the valley of the Lower Burdekin. The greatest elevations are found at the northern extremity of this range, where it attains near the coast a height of 5400 feet, while between these and the head of the Gulf of Carpentaria is an elevated hilly tract about 2500 feet above the sea. The inland slopes of these mountains are generally very fertile, and, towards the north, are often distinguished for their exuberant vegetation.

Passing west of the Gulf of Carpentaria, we find an extensive tract of high table-land, which appears to attain its greatest elevation where the Alligator River flows between precipitous walls, said by Leichardt to be of the enormous height of 1800 feet.1 This plateau becomes lower

1 It is doubtful whether these figures are correct, as they are only founded on an estimate of Leichardt. Unfortunately, still more erroneous ideas have become current as to this part of Australia, owing to the map illustrating Leichardt's Journal giving 3800 feet as the height of these precipices, and these extravagant figures have been repeated in many maps and referred to by many writers down to the present day. There can be little doubt, however, that it is an engraver's or copyist's mistake, and ought to be 1800 feet, and even that is a mere guess and liable to be much exaggerated. This was pointed out by Mr. Wilson, the geologist of the North Australian Expedition of 1855-56, first in the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. i. p. 230, and again in the Journal of the same society, vol. xxviii. p. 137 (1858); but no one seems to have taken any notice of his views—another instance of how difficult it is to get an error corrected which has once been promulgated in print on apparently good authority. Twenty years have now passed, and it is time that the mistake should be again pointed out. Messrs. Gregory and Wilson passed across the country about eighty miles south of the point referred to, and they nowhere found it more than about 1600 feet above the sea, and none of the rocky valleys they encountered were more than 600 feet deep. Precipices of 3800 feet exist nowhere but in the vicinity of great mountain ranges, and certainly imply a maximum height above the sea of double that of the precipice, or 7600 feet. In the Blue Mountains, where the plateau reaches from 3000 to 4000 feet above the sea, the celebrated precipices and ravines of Govat's Leap are about 1000 or 1500 feet, and nothing surpassing them is known in Australia. In 1862 M'Douall Stuart passed across the same table-land nearly parallel to Leichardt's track, and only forty miles distant from it. His journal shows that the country was here no higher than Mr. Wilson found it a little farther south, and the highest cliffs he mentions are from 250 to 300 feet. If we turn to Leichardt's own Journal, expecting to find some full description of what would be one of the greatest geographical marvels in all Australia, we discover nothing whatever about it. On the map we find the "steep walls 3800 feet high" indicated as occurring between his stations of November 10th and November 11th. But on these dates we find no mention of anything extraordinary; but on November 17th a great valley is reached, the descent into which is very difficult and required a considerable circuit, owing to the steep rocky walls estimated at 1800 feet high. The map, we find, was drawn from Leichardt's materials by Mr. T. A. Perry, the Deputy Surveyor-General of New South Wales, and was engraved in London by Arrowsmith, and there is no statement that Leichardt supervised or corrected either the draft map or the engraving, which, indeed, he could have had no opportunity of doing, as he had started on his last ill-fated expedition when his Journal was published in London. It is now, we think, fully time that this mythical "3800 feet" should be entirely expunged from our maps and geographical works, and that even the sufficiently marvellous "1800 feet" be inserted as merely an estimate and not a measurement. It is necessary to call attention prominently to this error, because, even in a work of such high authority as the new edition of the Encyclopœdia Britannica, in the article "Australia," we find the old statement repeated as an established geographical fact, as follows:—"On the north side of the continent, except around the Gulf of Carpentaria, the edge of the sandstone table-land has a great elevation; it is cut by the Alligator River into gorges 3800 feet deep."

C

towards the Roper and Victoria Rivers, and then gradually emerges southward into the great central plains; but much of it appears to be of exceeding fertility, and full of varied and picturesque scenery.

Amongst the least known regions are the highlands of the north-west, which are intersected by the Victoria River flowing into the Queen's Channel, and separated southwards, by a low ridge, from the desert lowlands of the interior. Northwards, the land descends in broad terraces, interrupted by mountain chains, and forming

fruitful plains watered by the forks of the Victoria, while desolate lowlands again stretch away eastwards.

The west Australian highlands are divided into two sections, which, though connected together, are of very different formation. The northern division consists of wide and mostly fertile plains, crossed by isolated chains running east and west, and intersected by the valleys of the Ashburton, Gascoyne, and Upper Murchison, all flowing westwards to the Indian Ocean. The southern section, beginning with the Middle Murchison, presents a very different aspect, of a character highly unfavourable to the development of social culture. With the exception of a few small oases with water, grass, and timber, the broad plains are here extremely unproductive, being almost entirely destitute of fresh water, and overgrown with thickets and low brushwood. There are but few mountain ranges, the elevations consisting more frequently of low disconnected hills. A prominent feature of the land are the large salt basins, containing either brackish water or else nothing but mud largely impregnated with alkalies. Many of these basins doubtless form connected river systems, though certainly of the most imperfect and defective character, such as those of the Upper Swan River, and of the Blackwood in the south; but in most cases their claim to be regarded as such has not yet been established. The western limits of these highlands towards the coast form a series of ridges, of which the most conspicuous is the Darling Range.

Lastly, the south Australian highlands, which are the least in extent, stretch from the south coast northwards along the eastern shores of the St. Vincent and Spencer Gulfs; and are limited eastwards by the lowlands, and on the north by the lacustrine region centering in Lake Torrens. Here the most important chain is the Flinders Range.

4. The Interior.

The interior of Australia consists mainly of lowlands, which penetrate even to the coast at certain isolated points where the outer ranges are separated from each other. These lowlands are almost uniformly of an extremely unfavourable character, forming some of the most forbidding and desolate regions on the face of the globe. The flat and, rarely, hilly plains, though often interrupted by detached rocky mountains, have mainly a sandy, clayey soil of a red colour, more or less charged with salt. They are covered chiefly with thickets and "scrub" of social plants, generally with hard or prickly leaves. This "scrub," which is quite a feature of the Australian interior, is chiefly formed of a bushy Eucalyptus which grows something like our osiers to a height of eight or ten feet, and often so densely covers the ground as to be quite impenetrable. This is the "Mallee scrub" of the explorers; while the still more dreaded "Mulga scrub" consists of species of prickly Acacia which tear the clothes and wound the flesh of the traveller.

There is here, moreover, an extraordinary deficiency of water, and a total absence of springs; nothing in fact but the rare heavy downpours converting the land for the time being into an impassable swamp, which the long-continued ensuing drought again reduces to a stony consistency. Still there are sections of these lowlands presenting special individual features, besides which there exists in the very heart of the continent a connected series of upland plains and ranges, which may be grouped together as forming collectively a central Australian highland region.

In the country immediately north of Spencer's Gulf is an extensive area which may be called the lake district of Australia, and which is nearly a thousand miles in

length from south-east to north-west. First we have Lake Torrens, more than a hundred miles long, but not very wide. Lake Eyre farther north is much larger. To the west is the extensive Lake Gairdner, and to the east of Lake Eyre are Lakes Blanche, Gregory, and several others. All these lakes are salt, and are subject to great fluctuations in size, grassy plains being found in some years where extensive sheets of water at other times cover the country. Around them extends for the most part the dreariest country imaginable, consisting of sandy ridges, either bare or covered with scrub, and almost entirely without permanent supplies of water, although in some places small permanent springs have been discovered. Far to the north-west of Lake Eyre is the equally extensive Lake Amadeus, bordered by salt-crusted flats of treacherous mud which have proved disastrous to many of the explorers. To the north and north-west of Lake Eyre for ten degrees of latitude, the country is almost wholly destitute of permanent water, and this region is also marked by the presence of the "spinifex" or porcupine grass (Triodia irritans). This is a hard, coarse, and excessively spiny grass, growing in clumps or tussocks, and often covering the arid plains for hundreds of miles together. It is the greatest annoyance of the explorer, as it not only renders travelling exceedingly slow and painful, but wounds the feet of the horses so that they are often lamed or even killed by it. The tussocks are sometimes three or four feet high, they are utterly uneatable by any animal, and where they occur water is hardly ever to be found.

If we draw a line from the western entrance of Spencer's Gulf on the south, to the mouth of the Victoria River in the north, we shall have on the west side of this line an almost unbroken expanse of uninhabitable country reaching to the settlements of West Australia. This vast area, extending from the north-west coast to the shores of

the great Australian Bight, is, roughly speaking, about 800 miles square. It has been crossed by several explorers with the greatest difficulty; and although a few oases have been found at long intervals, its general character is that of a waterless plain interspersed with low and sometimes rocky hills, at times absolutely barren, but usually covered with dense scrub or with the spiny Triodia.

A little to the east of the same line, and nearly in the centre of the continent, is a group of highlands, the Macdonnel Ranges and Mount Stewart, among which are grassy plains, fertile valleys, and more or less numerous watercourses. These are continued towards the north by the Murchison and Ashburton Hills, till they merge into the northern plateau of the Victoria and Roper Rivers. Farther east is an unknown country, most of which is probably arid and uninhabitable where it is not absolutely desert, and this stretches away till we reach the more fertile plains of Western Queensland.

It is thus evident that Australia abounds in basins of inland water, which, however, are mostly saline and are seldom flooded all the year round. They also differ from other lakes, in so far as they depend for their supplies mainly on the rainy monsoons, possessing no regular influents or even surface springs, and lying mostly in the centre of waterless, stony deserts. For Australia, in this respect more African than Africa itself, is essentially the land of wastes and steppes. As its most elevated regions lie to the windward of the continent, the trade-winds in surmounting these lofty ranges already lose a large portion of their moisture before reaching the interior. Hence the steppes begin close to the western slopes of the eastern coast ranges. At first well-watered grazing grounds, such as the Darling Downs, they gradually become drier and drier as we proceed westwards. The air is further heated in the heart of the continent by

contact with the burning soil, preventing the condensation of the humidity that still remains in the easterly winds. Of constant recurrence in the journals of the wearied travellers crossing the interior of the continent is the remark, that the clouds gather, the heavens become overcast, threatening a downpour every moment, but always with the same disappointing result. The clouds disperse before the vapours are sufficiently condensed to produce rain. The heated ground raises the temperature of the superincumbent air to such a degree that the already perceptible moisture is again dissolved into vapour. The fatal consequence is, that Australia possesses nothing but coast streams or intermittent watercourses in the interior, and although it appears on the maps as a large island, the heart of the country is occupied by deserts as arid as those of the great continents.

5. Rivers.

Foremost among the river-valleys is the region of the Murray and Darling in the south-east of the continent, forming jointly a water system worthy to be compared with those of the Old and New Worlds. Like the Amazon, it sends out forks and ramifications crossing many degrees of latitude and longitude, and it gathers its waters from the most opposite quarters. All the inland rivers of East and South Australia, between the 26th and 36th parallels drain into one or other of the two main streams, whose joint course stretches across thirteen degrees of the meridian, forming a triangle the points of which might be represented in Europe by the cities of Turin, Königsberg and Belgrade. The volume of water flowing through the winding beds of these rivers and creeks, though at times swollen to enormous proportions, is usually far from considerable, and occasionally for months together very limited.

As in this continent generally, the scenery of the Murray is cast on very grand lines. Pleasant, undulating, and graceful curves stretching away for interminable distances, and retaining the same character for days together, are succeeded in one place by bold mountain masses, in another by boundless plains, vast as the ocean, and

THE MURRAY.

relieved only by the shimmering and hazy reflection of some distant tree, or by the equally deceptive image of a few stunted shrubs exaggerated out of all proportion by the mirage and other atmospheric illusions. Seen from its high banks, the river presents almost everywhere the picture of a majestic stream, the grandeur of which is often enhanced by the numerous channels, lakes, and lagoons adding animation to the surrounding riverain scenery.

Nevertheless, this region consists largely of dreary, waterless plains, generally covered with dense bush, rarely relieved by low woodlands and open glades. It forms two distinct sections, that of the Murray on the south and the Darling on the north. The former, which is the most important of all Australian streams, rises in the Warragongs or Australian Alps, and after receiving the waters of the Goulburn and Loddon, is joined by the Murrumbidgee, swollen by the Lachlan from the northeast, whenever that stream does not run dry. A little farther on it forms a confluence with the Darling, also from the north-east, and which, like the Murray, is itself formed by the union of two head streams, collecting all the waters flowing from the western slopes of the New England and other coast ranges.

On the east coast the Fitzroy and Burdekin rivers are the most important, the latter draining an extensive area in a north and south direction, and about 200 miles inland. The northern rivers are numerous, but not important. The Flinders, which enters the head of the Gulf of Carpentaria, is the most extensive, its tributaries having their sources in the elevated country about 300 miles to the south and south-east. In the north-west the only rivers of importance are the Roper and Victoria, which flow through an elevated country, through deep gorges and among magnificent scenery, and the lower courses of which are navigable for considerable distances. On the west coast there are no rivers of importance; for though several of them have courses of 200 or 300 miles, they scarcely exist in dry seasons, and are only navigable for boats for very short distances. In the south there is a complete absence of rivers from near King George's Sound to Spencer's Gulf.

The drainage of the interior is effected by numerous creeks and watercourses which only run after periods of

rain, and which either lose themselves in the desert or terminate in some of the depressions which form the salt lakes. The most extensive of these inland rivers are the Barcoo and the Finke, which flow into Lake Eyre from the north-east and north-west respectively. These drain a great extent of country, but usually form mere series of water-holes.

The rivers of Australia are, almost without exception, subject to excessive irregularities of drought and flood. In the eastern half of the continent especially, great floods occur at long intervals, when rivers rise suddenly, overflow their banks, and carry devastation over wide areas. At other times the rains fail for years together, and rivers which are usually deep and rapid streams become totally dried up. The state of the country is then deplorable; not a blade of grass is to be seen, and cattle perish in great numbers. A tract of country may thus be described as a flooded marsh, a fertile plain, or a burnt-up desert, according to what happens to be the character of the seasons at the period when it is visited.

6. Climate of Australia.

Although Australia is such an extensive country, and is divided between the tropical and temperate zones, it has nevertheless much less variety of climate than might be supposed. It may generally be described as hot and dry, and, on the whole, exceedingly healthy. In the tropical portions the rains occur in the summer, or from November to April; while in the temperate districts they are almost wholly confined to the winter months. The greatest quantity of rain falls on the east coast, being 50 inches at Sydney, diminishing considerably inland, so that at Bathurst (96 miles from the sea) it is only 23 inches, at Deniliquin (287 miles) 20 inches, and at Wentworth

(476 miles) 14 inches. In the south, at Melbourne and Adelaide, the rain is about 25 and 20 inches; in Western Australia about 30 inches; in Queensland from 40 to 80 inches on the coast, but much less at a moderate distance inland. From Rockingham Bay northwards the rains are tropical. The temperature of course varies greatly with latitude and position. In the extreme south, at Melbourne, the temperature varies from about 30° to 100° Fahr. in the shade, the mean being 58°, or the same as Lisbon. At Sydney the mean is about 5° higher. At Adelaide, though farther south, the mean temperature is somewhat greater than at Sydney; while at Perth, farther north, it is about the same. South Australia and Victoria, and in a less degree New South Wales, are subject to hot winds from the interior of a most distressing character, resembling the blast from a furnace. The thermometer then rises to 115°, and occasionally even higher when extensive bush fires increase the heat. Sometimes the hot winds are succeeded by a cold south wind of extreme violence, the thermometer falling 60° or 70° in a few hours. In the desert interior these hot winds, nearer to their source, are still more severe. On one occasion Captain Sturt hung a thermometer on a tree shaded both from the sun and wind. It was graduated to 127° Fahr., yet the mercury rose till it burst the tube! The heat of the air must therefore have been at least 128°, probably the highest temperature recorded in any part of the world, and one which, if long continued, would certainly destroy life. The constant heat and drought for months together in the interior are often excessive. For three months Captain Sturt found the mean temperature to be over 101° Fahr. in the shade; and the drought during this period was such that every screw came out of their boxes, the horn handles of instruments and combs split up into fine laminæ, the lead

dropped out of pencils, their hair and the wool of the sheep ceased to grow, and their finger-nails became brittle as glass.

Notwithstanding the extreme heat and sudden changes of temperature, the climate of most parts of Australia is universally admitted to be exceptionally healthy. Epidemic diseases are almost unknown, and the death-rate for the whole white population is under 19 per thousand, that of England and Wales being 25. On the east coast, sea-breezes during the day render the heat less oppressive, while in the winter westerly winds prevail. On the west coast, the heat and dryness of summer are also tempered by sea-breezes and by occasional showers and thunderstorms: while in the four winter months north-west winds prevail, accompanied by abundant rains. Although subject to great occasional irregularities, the climate of Australia in the temperate zone is on the whole equable, storms and electrical disturbances being less frequent than in England.

7. Climate of New South Wales.

Mr. H. C. Russell, the Government Astronomer for New South Wales, having recently published a volume devoted to the meteorology of this colony, we will give a summary of his interesting results in further illustration of the specialties of Australian climate.1

1 The self-registering tide-gauge established by Mr. Russell at Newcastle, near Sydney, has been the means of making some interesting observations on the rate of propagation of vibrations caused by earthquake shocks. In May 1877 there was an earthquake on the coast of Peru, when ships at sea felt powerful vibrations (not waves). Mr. Alfred Tylor, F.G.S., having been making experiments on the rate of transmission of such vibrations, wrote to Mr. Russell to look at the register of his tide-gauge at a date specified, and was informed that unusual vibrations of the registering pencil had occurred at the time indicated. The rate of transmission of these vibrations across the entire Pacific Ocean was about five miles a minute.

Within the colony of New South Wales itself may be found a great range of climates—from the cold at Kiandra, where the thermometer sometimes falls 8 degrees below zero, and where eight feet of snow has fallen in a single month, to the more than tropical heat and extreme dryness of the inland plains, where frost is never seen, and the thermometer in summer often for days together reaches from 100° to 116°, and where the average annual rainfall is only 12 to 13 inches, sometimes even none at all falling for an entire year.

The climate of this part of Australia is beneficially affected by a warm equatorial current setting south along the coast. This furnishes moisture in the summer, and mitigates the cold of winter. Rain here comes from the east or south-east with great storms of wind, and it is sometimes so violent that on several occasions 20 inches have been known to fall in twenty-four hours. On the east of the mountains the average rainfall is 40 inches, and the number of wet days 102; while in the interior, on the west of the mountains, it is about 14 inches with 70 wet days.

The summer heat on the eastern watershed is less than in the interior, but to many persons it is more trying, because it is a moist tropical heat, whereas in the interior it is dry and bracing.

8. Winds.

In order to comprehend the nature and causes of the winds in this country, it will be well to consider, first, what would take place if the greater part of Australia were sunk beneath the ocean. The trade-wind would then blow steadily over the northern portions from the south-east, and above it a steady return current would blow to the south-east, while strong westerly and southerly winds would prevail over the southern half of the country.

Into this system of aerial currents Australia introduces an enormous disturbing element, of which the great interior plains, and the main chain of mountains running along the east coast, form the most active agencies in modifying the winds. The former, almost treeless and waterless, acts in summer like a great oven with more than tropical heating power, and becomes the chief motor force of Australian winds, by causing an uprush, and consequent inrush on all sides, especially on the northwest, where it has sufficient power to draw the north-east trade-wind over the equator and convert it into a northwest monsoon; which has the effect of obliterating the south-east trades properly belonging to this region. The north-west monsoon being heated in the interior, rises up and forms part of the great return current from the equator towards the south pole.

That there is a constant overhead current from northwest to south-east may be traced, day after day and month after month, by the small clouds which mark its lower limits passing in ceaseless streams to the south-east. The height of this current is generally about 5000 feet, but it is sometimes much lower, so that occasionally it is possible to fly a kite at Sydney, which rises into it and is carried away to the south-east, while the sea-breeze below is blowing from the east or north-east. These sea-breezes are also due, primarily, to the inflow towards the heated interior, but meeting with the mountain ranges they are usually diverted towards the south-west, and thus appear as north-east winds, a diversion partly caused by the friction of the great north-west current overhead. When the monsoon is most violent it carries off much of the sea-breeze with it, producing a depression of the barometer, when southerly winds rush in till the barometer rises again. Thunder and lightning usually follow these changes. The heated north-west monsoon has been

felt in Tasmania at a height of 5000 feet. In winter the heating influence of the interior ceases, the trade-winds move farther north, and the normal westerly winds prevail with storms and rain from the south.

The well-known southerly "bursters" are violent storms of wind occurring in summer (November to February), when the weather is fine and hot with a northeast breeze. If then the barometer falls fast in the forenoon, a "burster" may be expected before night, usually accompanied by thunder and much electrical excitement. Its approach is indicated by an appearance as if a thin sheet of cloud were being rolled up before the advancing wind. Clouds of dust, which penetrate everywhere, announce the coming of the wind, which reaches its greatest violence in an hour or two, varying from 30 to 70 miles an hour, though sometimes reaching 90, and on one occasion 150, when great damage was done. The change is sometimes very sudden. It may be a fresh north-east breeze, and in ten minutes a violent gale from the south. They usually end with a thunderstorm and rain. In the autumn (February) the rainfall accompanying these storms is often excessive. On the 25th of February 1873 nearly nine inches of rain fell in about the same number of hours. At Newcastle, on March the 18th, 1871, the heaviest rainfall ever recorded in Australia occurred; ten and a half inches of rain falling in two and a half hours, accompanied by a fearful squall of wind and rain with thunder and lightning. During the whole storm more than twenty inches of rain fell in twenty-two hours.

The hot winds, which are another remarkable feature of the meteorology of Australia, occur in New South Wales usually from three to seven or eight times during the summer; but many more pass overhead, their only effect being a rise in the temperature. The temperature

at Sydney varies from 80° to 110°, though it rarely reaches 100°. These winds are felt over the whole east and south of Australia, and they are even said to be distinctly perceptible as far as New Zealand. The hot wind generally comes on in the forenoon and lasts all day; but sometimes it only blows for an hour or two. It is preceded by very fine weather, with a gradually falling barometer and a diminishing sea-breeze. It sometimes passes away quietly, but is more usually ended by the southerly "bursters" already described. Hot winds are oppressive, but not absolutely injurious to health, yet their effect on vegetable life is very marked. Plants all droop, and those with tender leaves shrivel up as if frostbitten; and there is one instance on record in which all the wheat was destroyed over 30 miles of country on the Hunter River. In Victoria, and especially in South Australia, the hot winds are more frequent and last longer, and their effects are more injurious. They are evidently produced by the sinking down to the surface of that north-westerly current of heated air which, as we have seen, is always passing overhead. The exact causes that bring it down cannot be determined, though it evidently depends on the comparative pressures of the atmosphere on the coast and in the interior. Where from any causes the north-west wind becomes more extensive and more powerful, or the sea-breezes diminish, the former will displace the latter and produce a hot wind till an equilibrium is restored. It is this same wind passing constantly overhead that prevents the condensation of vapour, and is the cause of the almost uninterrupted sunny skies of the Australian summer.

9. Snow.

There is only one instance known of snow having fallen so as to lie on the ground in Sydney. On June

28, 1836, it snowed for half an hour, and lay on the ground in places for an hour. In other parts of the colony, however, the case is different. On the southern mountains and table-lands three feet of snow sometimes falls in a day, and in 1876 a man was lost in the snow on the borders of Gipps Land and New South Wales. In the Maneroo plains east of the Australian Alps in July 1834 a snowstorm lasted three weeks, and on the mountains the snow lay from 4 to 15 feet deep, burying the cattle in groups. The higher parts of the railway from Sydney to Bathurst have been seen covered with snow for 40 miles continuously. At Kiandra in the Australian Alps, one of the highest and coldest towns of New South Wales and 4600 feet above the sea, snow falls continually from May to November, sometimes for a month together. Many of the higher mountains are covered with snow all the winter, and in many of the valleys and ravines near the summits snow lies in patches all the summer. Below the summit of Mount Kosciusko a bed of snow 40 feet thick was found on the longest day, and it accumulates in such large masses that some may always be seen from any elevated point commanding a good view of the higher mountains. On Mount Kosciusko it even forms glacier masses in the deep ravines, which are more or less permanent. Even at heights of 5000 feet, in situations favourable for the accumulation of snow, it remains all the year. Yet the highest mountain (7175 feet) is considerably below the line of perpetual snow for this latitude, since on Mont Blanc, nine degrees farther from the equator, the snowline is 8500 feet above the sea. The difference is probably due to the presence of the warm oceanic current supplying abundance of moisture from below, while the rapid radiation through a pure and usually clear atmosphere above, lowers the temperature so as to condense

D