THE REVOLT OF DEMOCRACY

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE

THE REVOLT OF DEMOCRACY

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Social Environment and Moral Progress

Cassell & Co., Ltd., London, New York Toronto and Melbourne

THE REVOLT OF DEMOCRACY

BY

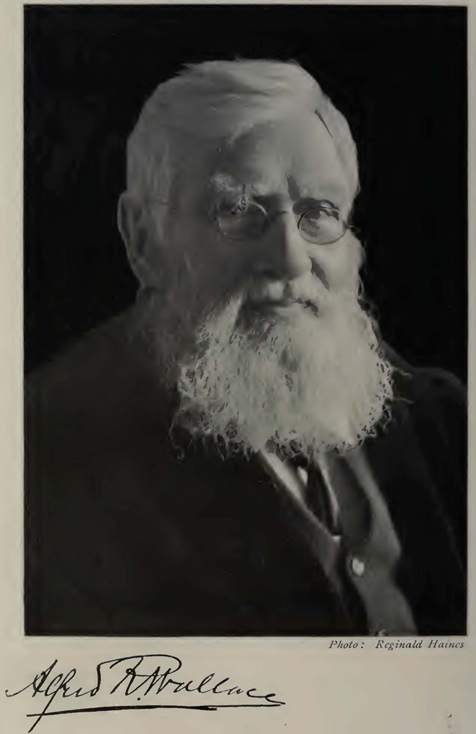

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE

O.M., D.C.L.OXON., F.R.S., ETC.

WITH THE

LIFE STORY OF THE AUTHOR.

BY JAMES MARCHANT, F.R.S.Edin.

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1913

CONTENTS

PAGE

| PAGE | ||

| LIFE STORY OF THE AUTHOR | vii | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| 1. | INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| 2. | THE DAWN OF A NEW ERA | 7 |

| 3. | THE LESSON OF THE STRIKES | 11 |

| 4. | WHAT THE WORKERS CLAIM AND MUST HAVE | 14 |

| 5. | A GOVERNMENT'S DUTY | 22 |

| 6. | POPULAR OBJECTIONS, AND REPLIES TO THEM | 35 |

| 7. | THE PROBLEM OF WAGES | 40 |

| 8. | SELF-SUPPORTING WORK THE REMEDY FOR UNEMPLOYMENT | 53 |

| 9. | THE ECONOMIES OF CO-ORDINATED LABOUR | 60 |

| 10. | THE EFFECT OF HIGH WAGES UPON FOREIGN TRADE | 68 |

| 11. | THE RATIONAL SOLUTION OF THE LABOUR PROBLEM | 74 |

The Life Story of the Author

LIKE a watchman on a lonely tower, with keen vision and responsive mind and heart, Alfred Russel Wallace has observed more change and development of scientific and social opinion and a higher advance of the tide of knowledge across the shores of human speculation and ignorance than any living scientist. Yet, unlike that solitary watchman, he himself has been, and is, an active pioneer of scientific revelation. For a long time he was the voice of a system of truths so far ahead of the attainments of his generation that to his contemporaries much of his teaching seemed rank heresy and almost blasphemy; but, like a true prophet, he has had not only the patience but the opportunity given him to see most of his discoveries and his teachings incorporated into the stately palace of truth.

When he was born in 1823, our world, as we know it to-day (a composite thing of multitudinous energies thirled to the service and utility of mankind) had scarcely come into existence. He has seen the formidable

and mysterious powers of electricity enslaved to the service of the ordinary affairs of daily life, and has watched with glowing interest the coming of the motor-car and the flying machine. He has lived under five British sovereigns, has witnessed the spread and development of railways, and the adoption of steam for navigation, the supersession of the wooden walls by the steel bulwarks of Britannia, and other changes beyond record in the practical application of scientific discoveries. When he was a boy, photography was a plaything, the electric telegraph a mere experiment, the penny post unknown, the newspaper a luxury of the few, the material world, as a whole, a vast and impenetrable wilderness, continent separated from continent by wide-stretching seas, traversed only by daring spirits.

He has seen the material world of mere geography shrink till now it can be girdled by the commonest message in a matter of minutes; he has seen the newspaper in every home, the simplest word of love carried the whole empire over for one penny, the criminal and the outcast treated more like sinners to be redeemed who are often "more sinned against than sinning."

To have seen so much is to make any man a centre of human interest. To hear the now aged naturalist tell of what his life has been awakens vivid response even in the heart of the

most apathetic. But to know that all the while he was no shirker in life's upward march, but himself a profound thinker, a ceaseless searcher, a sagacious discoverer, and that most of his theories and opinions, which had been scouted by thinkers for many years, are now sound and current coin in the treasure-house of true science, is gratefully to acknowledge him as one of the greatest sons of his age and a shining benefactor for all time.

His father, Thomas Vere Wallace, a briefless lawyer, was also an experimenter. He had a family of nine children. It was little satisfaction that the number of the Muses was the same, for the Muses were not confronted by the problem of bread-and-butter which perturbs a human family. He was not of a practical turn of mind, and his private income was not sufficient to provide for the necessities of his children. But he was a man of literary taste, and he embarked upon a venture of a very speculative nature, namely the publication of an Art Magazine, which wellnigh exhausted what means he still possessed. He therefore had to leave London, and transferred his household goods and gods to the town of Usk in Monmouthshire, where he tried the new experiment of economy. Here Alfred, the last but one of the nine, was born, and here he spent the first four years of his life, with no need to go outside of his own house for a plentiful supply of playmates. In 1828 the

family made another move—to Hertford—and there they remained for about nine years. At the grammar school of that provincial town young Wallace received the only regular education, in the popular acceptance of the term, which was to be the basis of his wider intellectual development.

With him it is different than with most men of note, for his contemporaries, having all now passed into the greater silence, there is no source of anecdotal reminiscence and estimate of his boyhood left, except his own memory. It is always of pleasing interest to know what a boy's comrades thought of him, what he did or said to make the keen critics of the schoolroom or the playground take note of him, and wherein, if anywhere, he differed from his fellows. One thing, at any rate, is certain: the mode of formal instruction under the shadow of which he passed, in those swift enough years at the Hertford Grammar School, was not of a sort to benefit deeply such a mind as his. Geography was a list of towns and rivers; history little more than tables of dates, all to be learned by rote, without regard to the causal origins of such a thing as a country, a kingdom, a river, or the achievement of human effort which gave memorableness to the figures of a calendar. To such a youth, who no doubt from the first looked over the shoulder of to-day back into the misty yesterdays out of which to-day emerges,

asking the Why as anxiously as the What of things, this schooling must have been very unsatisfying. As he himself says, "The labour and mental effort to one who, like myself, has little verbal memory was very painful; and though the result has been a somewhat useful acquisition during life, I cannot but think that the same amount of mental exertion, wisely directed, might have produced far greater and more generally useful results." It was also most natural that the eclectic method of historical study should have most strongly appealed to him, so that he can say, "Whatever little knowledge of history I have ever acquired has been derived more from Shakespeare's plays and from good historical novels than from anything I learned at school."

To watch men and women who thought, toiled, and achieved, rough-hewing life's obstacles into instruments of life's victories, is of greater moment than reading tombstone records or having one's name written up on a schoolroom slate. The method of visualised humanities, breathing, living and doing, is ages in advance of that which thinks of history as being mainly great men sitting in their bones in an anatomical museum, labelled "History." Latin grammar, and, in the higher classes, Latin translation—these were the subjects chiefly taught.

But Wallace's life was, fortunately, independent of, and lifted out of such a cramping

environment by other circumstances, which such narrow schemes could not control. His father was a book-lover and belonged to a book club, and the soul of the lad was enriched by a constantly flowing stream of suggestive and elevating literature. A bookman's home is the best of universities. His father frequently read aloud in the evenings from such books as Mungo Park's "African Travels," along with those of Denham and Clapperton. Then there was the sunshine that scintillates through Hood's "Comic Annual," and the grave and gay of "Gulliver's Travels" and of "Robinson Crusoe," and the deep-toned gravity and humour, with knowledge of the human heart unparalleled, in "The Pilgrim's Progress." Thus the companionship and wisdom of such creations of human genius enlightened the ready mind of the growing youth by the evening fire of that Hertford home. His father for some part of his residence in Hertford was librarian of the town library, and there, in the quickening presence of books, young Wallace spent many of his leisure hours.

When he left school, at the age of fourteen, he stayed for a short time with his elder brother John, who was at that time apprenticed to a builder in London. It was at this period that he first came in contact with people of advanced political and religious opinions, and read such works as Paine's "Age of Reason." He also met followers of Robert Owen, the founder of

the Socialist movement in England. Robert Owen's fundamental principle was that the character of every individual was formed for him, and not by himself: first, by heredity, which gives him his mental disposition with all its powers and tendencies, its good and bad qualities; and, secondly, by environment, including education and surroundings from earliest infancy, which always modify the original character for better or for worse.

Young Wallace, whose upbringing had been strictly orthodox, was greatly impressed by these doctrines; and the ideas they inspired, though latent for fifty years, no doubt largely influenced his thoughts and his writings when he ultimately turned his attention from purely scientific to social and political subjects.

After a stay of a few months in London he joined his eldest brother William, who was a surveyor; and for the next four years (1837 to 1841) they were occupied together in surveying in the counties of Bedfordshire, Herefordshire, Radnorshire, and Brecknockshire. Some of this work was in connection with the various Enclosure Acts, by which the landlords obtained powers to enclose waste lands and commons, under the pretext of bringing them into cultivation. The result of these measures was that the cottagers were deprived of the means of keeping their few cattle, pigs, or ponies, while the enclosed land was often not cultivated at all, or, in the course

of time was converted into building land or into game preserves, so that the intention of the Acts of Parliament was ignored, and the poor people were driven to the towns, where, unfit to compete, they sank into the deeper poverty of slumdom.

Some of the surveys had to do with new railways which were being projected all over the country at that time, many of them doomed never to come into being, and many being mere clap - trap schemes of money - sucking adventurers.

It was owing to this open-air life, with plenty of leisure amidst beautiful country, that Wallace's observant mind was drawn into loving observation, which developed into more than companionship with the flowers and insects which everywhere abounded in such vast variety.

From such close interest he soon passed on to a serious study, in pursuit of which he commenced to form a scientific collection of the wild flowers and the insects he met with.

During his residence in Neath in 1841 he began to extend his knowledge in physics, astronomy, and phrenology, that half-blind groping after a greater science, taking advantage of popular lectures on those subjects and of such books as he could obtain.

In 1843 his father died, and in the following year there being then little in the way of surveying to do, Wallace obtained a situation as drawing-

master at the Collegiate School at Leicester. His two years' residence in this town was to have an important influence upon his future career, for it was here that he first met Henry Walter Bates, with whom he commenced his tropical travels four years later—so momentous not only for himself, but for the world. It was here also that he read Malthus's "Principles of Population." This pioneer work, after his long study and observation of tropical fauna, supplied the inspiration which clinched the theory of evolution he originated in 1858.

At this time one other important event happened which was to influence his ideas in later years, namely, a demonstration of the phenomenon of mesmerism, which interested him so much that he practised, and eventually succeeded in mesmerising some of his pupils.

After remaining in Leicester for two years, Wallace returned to Neath, where he and his brother John started in business as architects and builders. Hither they brought their mother and sister to live with them.

He was now twenty-three years of age, and over six feet tall. He had acquired a large store of varied knowledge, and made his first appearance as a lecturer. He delivered a series of expositions of scientific subjects, dealing mainly with physics, at the Neath Mechanics' Institute, the building which he and his brother had designed and supervised. He also made his first essays at

B

literature, and wrote papers on botany and on the Welsh peasantry.

His letters of this period throw an interesting light not only upon his own thoughts but upon the problems which were occupying the minds of scientific thinkers. He refers to the writings of Lyell, and to Darwin's "Journal of a Naturalist," Humboldt's "Personal Narrative," "The Vestiges of Creation," and Lawrence's "Lectures on Man." In a letter to Mr. Bates, dated 1847, he writes:

"I begin to feel rather dissatisfied with a mere local collection; little is to be learnt by it. I should like to take one family, to study thoroughly, principally with a view to the theory of the origin of species. By that means I am strongly of opinion that some definite results might be arrived at." Eleven years later he gave to the world those "definite results" of his study in the theory of "Evolution by the Survival of the Fittest."

Bates and Wallace finally decided to go to the tropics to study the birds and insects, and to support themselves by their collections. They, therefore, sailed from Liverpool in April, 1848, in a barque of one hundred and ninety-two tons, and arrived in Para after a voyage of twenty-nine days.

The four-and-a-half years which Wallace spent in South America have been fully described in his "Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro." In

a letter describing his impressions of the tropics he wrote:

"There is one natural feature of this country the interest and grandeur of which may be fully appreciated in a single walk; it is the 'virgin forest.' Here no one who has any feeling of the magnificent and the sublime can be disappointed; the sombre shade scarce illumined by a single direct ray even of the tropical sun, the enormous size and height of the trees, most of which rise like huge columns a hundred feet or more without throwing out a single branch, the strange buttresses around the base of some, the spiney or furrowed stems of others, the curious and even extraordinary creepers and climbers which wind around them, hanging in long festoons from branch to branch, sometimes curling and twisting on the ground like great serpents, then mounting to the very tops of the trees, thence throwing down roots and fibres which hang waving in the air or, twisting round each other, form ropes and cables of every variety of size and often of most perfect regularity. These and many other novel features—the parasitic plants growing on the trunks and branches, the wonderful variety of foliage, the strange fruits and seeds that lie rotting on the ground—taken altogether surpass description and produce feelings in the beholder of admiration and awe. It is here, too, that the rarest birds, the most lovely insects and the most interesting mammals and reptiles are to be found. Here

lurk the jaguar and the boa-constrictor, and here amidst the densest shade the bell-bird tolls his peal."

He also relates his "unexpected sensation of surprise and delight" when he first met and lived with man in a state of nature—with absolutely uncontaminated savages. The wild Indians of the Uaupés were different from any he had previously met during two years' wanderings.

"They had nothing that we call clothes; they had peculiar ornaments, tribal marks, etc., they all carried weapons or tools of their own manufacture; they were living in a large house, many families together, quite unlike the hut of the tame Indians; but more than all their whole aspect and manner were different—they were all going about their own work or pleasure which had nothing to do with white men or their ways, they walked with the free step of the forest dweller, and except the few who were known to my companions, paid no attention whatever to us, mere strangers of an alien race. In every detail they were original and self-sustaining, as are the wild animals of the forests, absolutely independent of civilisation, and who could and did live their own lives in their own way as they had done for countless generations before America was discovered. I could not have believed there could be so much difference in the aspect of the same people in their native state and when living under European supervision. The true denizens of the

Amazonian forest, like the forest itself, are unique and not to be forgotten."

Amidst such scenes and among such people Wallace spent four-and-a-half years, often undergoing many hardships, exploring regions not before visited by white men; all the time collecting and studying the varied forms of life with which the forest glades and river banks abounded. He journeyed for many thousand miles in canoes on the great rivers, taking observations with sextant and compass of the courses of the Rio Negro and of the Uaupés which formed the basis for the first reliable map of those hitherto little known waterways.

His voyage home from Para in 1852 was both adventurous and disastrous. After having been at sea a week, the ship caught fire, and all hands had to take to the boats. The vessel, with all its cargo—including Wallace's collections, and most of his notes and journals—was completely destroyed, and the crew, with only their clothes and a small quantity of provisions, were tossed about in the middle of the Atlantic in two small boats for ten days. And when at last they were picked up by a passing vessel their danger and troubles were not yet over, for the ship on which they found themselves was very unseaworthy, and they encountered such violent storms that no one expected to reach land. His companions often wished themselves back in their open boats as being safer than the rotten and

overloaded vessel they were on. To add to their discomfort the ship was short of provisions, so that they had to endure semi-starvation during the rest of their tedious journey.

After eighty-two days at sea Wallace at last landed at Deal, with only the clothes he stood in, and a few sketches of palm trees and of fishes which he had saved out of the wreckage of so many hopes and labours. The valuable collection of four years' toil, the immediate results of patiently acquired knowledge, with the notes and journals of the greater part of his wanderings, were irretrievably lost. One can, without much imagination, picture his feelings under such a crushing blow. Luckily, through the foresight of his agent in London, his collections had been insured for a small amount, so that his losses financially were not so complete as he at first had feared; yet no monetary recompense could ever make up for the loss of the material and the records of his arduous exploration and research.

Soon after his return, with the aid of such scanty notes as he had saved, and the letters which he had sent home, he commenced to write the story of his travels, which was published in 1853. He also published an account of the palm trees of the Amazon, with illustrations from his own sketches.

In 1854 he again left Britain, and, travelling eastwards, arrived in Singapore, where he was to begin his eight years' wanderings amongst the islands

of the Malay Archipelago, an account of which is recorded in his most popular work of that name.

It was while staying in Sarawak, in 1855—where he became intimately acquainted with the celebrated Rajah Brooke—that he wrote his first article on the question of the Origin of Species. At that time, however, he had not grasped the complete solution of the problem. It was not till 1858, when at Ternate, suffering from an attack of fever, that, pondering over the subject, and recollecting Malthus's writings, the modus operandi of evolution flashed with creative vividness upon his mind, resulting in the paper which, together with Darwin's contribution, was to startle the scientific and religious worlds, and set ablaze the fires of a controversy which burned for many years, ere the doctrine of "survival of the fittest" was finally accepted by the world at large.

Wallace sent his paper to Charles Darwin, with whom he had corresponded about the previous article. Darwin, as the result of long and laborious study, had already arrived at the same conclusions, and had even taken his friends Lyell and Hooker into his confidence; but in spite of their advice and their fears that he might be forestalled, he wished to collect still more evidence to support his theory before making it public. On receiving Wallace's paper he wrote to Sir Charles Lyell: "Your words have come true with a vengeance—that I should be forestalled. I never saw a more striking coincidence."

Darwin who had already written a large part of a book dealing with his conclusions, was naturally much troubled as to what he should do. In another letter to Lyell he wrote: "I would far rather burn my whole book than that Wallace or any other man should think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit."

Ultimately, however, as a result of the advice of friends, who acted on their own responsibility, Mr. Wallace's essay and extracts from Darwin's manuscript were sent to the Linnean Society and read together before that Society in July, 1858.

The interest excited by the papers was intense. Many lingered after the meeting and discussed the subject with bated breath; but it was meanwhile too novel and too ominous to provoke that immediate opposition with which it met when its significance and effect were subsequently realised.

Wallace spent another eight adventurous and arduous years amidst scenes of tropical luxuriance and among the various savage and civilised races of mankind which inhabit the Malay Archipelago, before he returned home in 1862.

The collections he had sent home, comprising many thousands of insects, birds, and other forms of life, many of them previously unknown, together with the scientific papers already mentioned, had made him famous, and secured for him on his return not only his admit-

tance to many of the great learned societies, but the acquaintance and friendship of the scientific leaders of the day with whom he was soon to rank in undisputed parity. Amongst those with whom his intimacy deepened most fruitfully were Sir Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin.

With the former, Wallace had a long, amicable, but controversial discussion on the subject of the glacial origin of Alpine lakes, which Lyell was not then inclined to accept. At Sir Charles's house, where he was a frequent visitor, Wallace met many interesting people, amongst them being Professor Tyndall, Sir Charles Wheatstone, Mr. Lecky, and the Duke of Argyll, with all of whom he became on friendly terms.

With Charles Darwin, Wallace's relations were still more intimate and friendly, and their rivalry in their great discovery rather enhanced their friendship instead of producing that antagonism which, on smaller minds, would have been the result. Darwin frequently asked Wallace's help on points of difficulty in the application of the new theory, and though on several questions they disagreed, they always maintained the warmest admiration for each other.

In a letter to Wallace written in 1870, Darwin says:

"I hope it is a satisfaction to you to reflect —and very few things in my life have been more satisfactory to me—that we have never felt any jealousy towards each other, though in

some senses rivals. I believe I can say this of myself with truth, and I am absolutely sure that it is true of you."

In commenting on this letter Dr. Wallace writes:

"To have thus inspired and retained this friendly feeling, notwithstanding our many differences of opinion, I feel to be one of the greatest honours of my life."

The relations existing between Darwin and Wallace, to which we have already referred, are further exemplified by the affectionate love and warm admiration expressed in their letters to each other, and to mutual friends.

Referring to the proposal by Lyell and Hooker that Wallace's paper and an abstract of his own MS. should be read together before the Linnean Society, Darwin, in his autobiography writes:

"I was at first very unwilling to consent, as I thought Mr. Wallace might consider my doing so unjustifiable, for I did not then know how generous and noble was his disposition." ("Life and Letters," i. 85.)

While Wallace was still abroad, and before Darwin and he had met, Darwin wrote to Lyell of having received a letter from Wallace, "very just in his remarks, though too laudatory and too modest; and how admirably free from envy and jealousy. He must be a good fellow."

And in replying to Wallace, Darwin says:

"Before telling you about the progress of opinion on the subject (of 'The Origin of Species') you must let me say how I admire the generous manner in which you speak of my book. Most persons would, in your position, have felt some envy or jealousy. How nobly free you seem to be of this common failing of mankind! But you speak far too modestly of yourself. You would, if you had my leisure, have done the work just as well—perhaps better than I have done it." He ends "with sincere thanks for your letter and with most deeply felt wishes for your success in science, and in every way, believe me, your sincere well wisher."

And in writing to H. W. Bates, Darwin said: "What a fine philosophical mind your friend Mr. Wallace has, and he has acted in relation to me like a true man with a noble spirit."

Mr. Wallace differed from Darwin in believing that something more than Natural Selection was necessary to produce the higher intellectual qualities of man. This was the "heresy" to which he refers in a note to Darwin relating to an article by the latter, where he says:

"I have also to thank you for the great tenderness with which you have treated me and my heresies …"; to which Darwin replied, "Your note has given me very great pleasure, chiefly because I was so anxious not to treat you with the least disrespect, and it is so difficult to speak fairly when differing from

anyone. If I had offended you it would have grieved me more than you will readily believe." ("Life and Letters," iii. 134).

When Darwin heard from Mr. Gladstone that a Government pension had been given to Wallace—in which matter Darwin himself had been largely instrumental—he wrote to a friend, "Good heavens! how pleased I am."

This admirable desire to give each other the credit for the theory of Natural Selection is shown again and again in their letters, and it should be emphasised here.

"You ought not," Darwin wrote, "to speak of the theory as mine; it is just as much yours as mine. One correspondent has already noticed to me your 'high-minded' conduct on this head." ("More Letters," ii. 32.)

And Wallace, in a long letter, replied:

"As to the theory of Natural Selection itself I shall always maintain it to be actually yours, and yours only. You had worked it out in details I had never thought of years before I had a ray of light on the subject. … All the merit I claim is the having been the means of inducing you to write and publish at once."

Again in a letter referring to colouring of mammals and kindred subjects, Darwin wrote:

"I am surprised at my own stupidity, but I have long recognised how much clearer and deeper your insight into matters is than mine." ("More Letters," ii. 61.) And, when they dif-

fered over Sexual Selection, Darwin wrote: "I grieve to differ from you, and it actually terrifies me, and makes me constantly distrust myself. I fear we shall never quite understand each other." ("More Letters," ii. 85.)

Although Darwin and Wallace worked together so long and assiduously to develop and elucidate the theory they had originated, there were several points in its application in which they differed, and as these, though not in any way affecting the main principles of Natural Selection (on which they entirely agreed), have been seized upon and have been magnified by those who objected to the theory, we should dwell a moment upon them.

The principal differences may be stated thus: Darwin thought that Natural Selection alone was sufficient to explain the development of man, in all his aspects, from some lower form. Wallace, while believing that man, as an animal, was so developed, thought that as an intellectual and moral being some other influence—some spiritual influx—was required to account for his special mental and psychic nature. With regard to many cases of coloration, scent, or power of producing sounds, exhibited by the males of numerous animals, Darwin thought they were developed by the choice of the females for the males which were endowed by these qualities in the greatest degree, while those which had them in a less degree were not chosen, and so did

not so often produce offspring. Wallace, on the other hand, could find little or no evidence for this form of Sexual Selection. He maintained that all such colours, scents, etc., were produced by some operation of Natural Selection; that with insects a bright colour was often a warning to insect-eating animals that its possessor was distasteful; that the females required more protection, and therefore became coloured to harmonise with their surroundings. The males, owing to their habits and organisation, require less protection, and would therefore be modified no further than was sufficient to ensure the maintenance of the species.

Darwin explained the presence of Arctic plants in the Southern hemisphere and upon mountain tops in the tropics, by assuming that the tropical lowlands of the whole earth were cooled during the glacial epoch, so that these plants could spread to the localities where they are now found isolated. Wallace, from his study of the floras of oceanic islands, concluded that all these plants were introduced by means of aerial transmission of seeds or by birds, those seeds which were deposited in a suitable soil and climate germinating and in turn producing seeds by which the plant would spread over its new habitat.

The only other important matter on which these two great scientists differed was the question of the inheritance of acquired characters. Darwin always believed that the effects of use

or disuse, of climate, food, etc., on the individual were transmitted to the offspring; and Wallace himself accepted this theory for many years. But later, after Dr. Weismann * had shown how little evidence there was for such inheritance, he became convinced that acquired characters were not inherited.

All this shows in a very clear light the unselfish characters and singleness of purpose of two great minds, who set the dissemination of truth and the illumination of intellect above considerations of personal profit or reputation.

Amongst the celebrities with whom Wallace had frequent intercourse were Herbert Spencer, Thomas Huxley, Sir John Lubbock (afterwards Lord Avebury), Dr. W. B. Carpenter, Sir William Crookes, Sir Joseph Hooker, Sir Francis Galton, and many others not less famous.

In 1865 he married the eldest daughter of Mr. William Mitten, of Hurstpierpoint, the greatest living authority on mosses; and for the next five years lived in St. Mark's Crescent,

* Dr. Weismann writes ("Cambridge Comm. Essays"): "Everyone knows that Darwin was not alone in discovering the principle of selection, and that the same idea occurred … independently to Alfred Russel Wallace. … It is a splendid proof of the magnanimity of these two investigators that they thus, in all friendliness, and without envy, united in laying their ideas before a scientific tribunal; their names will always shine side by side as two of the brightest stars in the scientific sky."

Regent's Park. Becoming, however, tired of town life, and wishing to return to more congenial rural surroundings, he moved to Grays, in Essex, where he built a house close to an old overgrown chalk pit, which formed part of the garden.

During his residence here he wrote an important book, in two large volumes, with elaborate maps and illustrations, dealing with a subject on which he has always been admitted to be the leading authority, viz. "The Geographical Distribution of Animals." It was published in 1876, and still remains the standard work in the English language on that branch of science. From this time onwards he devoted most of his energies to writing—at first on purely scientific subjects, but later on more general topics, and especially on social and political questions, which gradually assumed a leading place in his thought.

Amongst other scientific works which he produced at this period were "Tropical Nature" and "Australasia" in 1878; "Island Life" in 1880. His most popular book, "The Malay Archipelago," was written while he still lived in London in 1869, and gave an account of his travels and adventures in the East.

In 1876 he found it necessary to give up his house at Grays, and, after living a few years at Dorking and at Croydon, he built a cottage at Godalming, where he remained from 1881 till 1889.

In 1881 a society was formed for advocating the Nationalisation of the Land, a subject in

which he took a deep interest, and he was elected president, retaining that office until the present time. There is no doubt that his early experiences while surveying, and his observations of the life and customs of many civilised and savage races, had left upon his mind those impressions which were to be developed into definite principles and beliefs when he devoted close attention to this and kindred subjects, at the time we are dealing with. With the exception of about eight years, he has spent the whole of his long life in the country, and his powers of keen observation have shown him the inconveniences, the hardship and the injustice often suffered by our rural population on account of the existing system of the private ownership of land, with the privileges which have grown up along with it.

In order to justify the formation of this society, and as a kind of programme of the work it had to do, he wrote a brochure entitled "Land Nationalisation: Its Necessity and Its Aims." This formed the starting-point of those political writings of his which have caused such mixed feelings amongst his scientific friends, many of whom deplore his views as unscientific and revolutionary, while others are no less unstinted in their praise and satisfaction.

The beginning of his social views he himself traces to Herbert Spencer's "Social Statics," which he read soon after his return from the Amazon. That part on The Right to Use the Earth

C

especially interested him, but under the influence of Mill and Spencer himself, he could not see how to work it out without an excess of bureaucracy. It was twenty-seven years later that the idea suddenly came to him that this difficulty "could be overcome by State tenancy of the bare land, with ownership by the tenant of all that was added to the bare land, so that the State was only ground landlord, and need not interfere at all with the tenant who held a perpetual lease." ("My life," ii. 34.)

In the book on "Land Nationalisation," he dealt at length with these subjects. But his objection to Socialism remained for about ten years later, because he could not see the way out of existing things and relations into the practical operation of socialistic principles. Bellamy's book gave him the final impact, and, he says, "I have been an absolutely convinced Socialist ever since." He was supported in his step by Spencer's teaching that all classes of society were almost equal morally and intellectually, in combination with Weissman's proof of the non-heredity of results of education, habit, use of organs, etc. Dr. Wallace has briefly defined Socialism as "the organisation of the labour of all for the equal benefit of all." This implies "the duty of everyone to work for the common good, and the right of each to share equally in the benefits so produced, and in those which Nature provides."

An address which he gave at Davos in 1896

on the invitation of Dr. Lunn, was the starting-point of the three last important works which he has written.

The first of these was "The Wonderful Century," which was an account of the marvellous advances in scientific knowledge and in invention which had taken place during the nineteenth century, of most of which he had been an eyewitness. The astronomical chapters of this book suggested the second, namely, "Man's Place in the Universe," which appeared in 1903. This latter work gave a most interesting study of the latest theories and facts with regard to the stellar universe, and the solar system and our position therein.

Dr. Russel Wallace arrives at the conclusion that this earth is the only inhabited planet in our solar system—probably, indeed, the only one inhabited by beings of a high order in the whole vast universal scheme; and that it is legitimate to suppose that the purpose of the universe was the production of man as a spiritual being. He showed that man's position, with regard to both the solar system and the whole universe, was unique, pointing to the probability of design and intention on the part of some Controlling Mind.

This idea was further developed and extended in his last scientific book "The World of Life," which appeared in 1911, its germ being the lecture which he delivered at the Royal Institution in the previous year. It was the act of collecting

the evidence of this work and "Man's Place in the Universe," from all the best scientific sources to which he had access, that forced upon him "the wonderful combination of conditions necessary for the possible development of life; and the still more marvellous and ever present manifestations of foreseeing, directing and organising forces, resulting in a World of Life culminating in Man, and in every detail adapted for the development of man's highest mental and moral powers."

"Thus," as he himself writes (letter to the present writer), "the completely materialistic mind of my youth and early manhood has been slowly moulded into the socialistic, spiritualistic, and theistic mind I now exhibit—a mind which is, as my scientific friends think, so weak and credulous in its declining years, as to believe that fruits and flowers, domestic animals, glorious birds and insects, wool, cotton, sugar and rubber, metals and gems, were all foreseen and foreordained for the education and enjoyment of man."

At a later date, in May, 1913, in another letter to the writer, Dr. Russel Wallace writes upon the possibility of a living organism being some day produced in the laboratory of the chemist from inorganic matter. He declares it to be impossible, because unthinkable, while even were it supposable that it should happen, it could not in any way explain Life, with all its inherent forces, powers and laws, which necessitate "a constantly

acting mind power of almost unimaginable grandeur and prescience, in the co-ordinated motions, action and forces of the myriad millions of cells, each cell consisting of myriad atoms and ions, which cannot be supposed to be all acting in harmonious co-ordination without some superior co-ordinating power.

"Recent discoveries demonstrate the need of co-ordinating power even in the very nature and origin of matter; and something far more than this in the origin and development of mind. The whole cumulative argument of my 'World of Life' is that, in its every detail it calls for the agency of a mind or minds so enormously above and beyond any human minds, as to compel us to look upon it, or them, as 'God or Gods,' and so-called 'Laws of Nature' as the action by willpower or otherwise of such superhuman or infinite beings. 'Laws of Nature' apart from the existence and agency of some such Being or Beings, are mere words, that explain nothing —are, in fact, unthinkable. That is my position!

"Whether this 'Unknown Reality' is a single Being, and acts everywhere in the universe as direct creator, organiser and director of every minutest motion in the whole of our universe, and of all possible universes, or whether it acts through variously conditioned modes, as H. Spencer suggested, or through 'infinite grades of beings' as I suggest, comes to much the same

thing. Mine seems a more clear and intelligible supposition as stated in the last paragraph of my 'World of Life,' and it is the teaching of the Bible, of Swedenborg, and of Milton!"

But in the very last paragraph of his "World of Life" he puts it as "a speculative suggestion," not as a definite scientific conclusion—"though it does seem to me to be one."

He concludes (in the letter to the writer) with this definite declaration:

"I write all this to show that, to me, if the chemist does some day show that living, developing 'life' was, and is now produced from inorganic elements, by and through ' natural laws,' it would not alter my argument one iota. 'Natural Laws' of such range and power are unthinkable, except as the manifestation of Universal Mind."

"The World of Life" moved the whole thinking world. It awoke as with the whip crack of a prophet's word the theological sleepers who had been drowsing in dogmatic ease, and that other loud boasting company of the blind who confidently thought they were wide awake when they denied the possibility of the very existence of a spiritual world and believed that "matter and force" were sufficient for all things, from cosmic dust to the writing of Hamlet.

This book was a revelation of the making of humanity, not starting from any basis of dogmatic preconception, but reasoned out by the clear mind of the trained natural observer, who,

turning his searchlight upon the footprints of the long-departed revealed, as the skilled hand drew aside the curtain, the picture of the actual world in process of evolution, thus, by a masterstroke, involving the exercise of all his powers, displaying eternal Providence, and "justifying the ways of God to man." The earliest result of the evolution theory seemed to be that earth was filled, not with the knowledge but with the terrors of God, and the human heart heard, if it could listen to their agonies and groans, of a struggling and suffering humanity punished for its own blindness and ignorance.

With Wallace, however, pain is the birth-cry of a soul's advance. "The stamp of rank in Nature is capacity for pain." Pain, he holds, is always strictly subordinated to the law of utility, and is never developed beyond what is actually needed for the protection and advance of life. This brings the sensitive soul immense relief. Our susceptibility to the higher agonies is a condition of our advance in life's pageant.

In this volume he summed up and completed his fifty years of brooding thought and long and patient labour on behalf of the Darwinian theory of evolution, extending the scope and application of that theory so as to show that it can and does explain many of the phenomena of living things hitherto considered to be outside its range.

Thus Dr. Wallace now believes that to explain

life and its manifestations God is a necessary postulate. And he here declares:

"The absolute necessity for an organising and directive Life Principle in order to account for the very possibility of these complex outgrowths. I argue that they imply, first, a Creative Power, which so constituted matter as to render these marvels possible; next, a Directive Mind, which is demanded at every step of what we term growth, and often look upon as so simple and natural a process as to require no explanation; and, lastly, an Ultimate Purpose, in the very existence of the whole vast life-world, in all its long course of evolution through the æons of geological time. This Purpose, which alone throws light on many of the mysteries of its modes of evolution, I hold to be the Development of Man, the one crowning product of the whole cosmic process of life-development; the only being which can to some extent comprehend Nature; which can perceive and trace out her modes of action; which can appreciate the hidden forces and motions everywhere at work, and can deduce from them a supreme over-ruling Mind as their necessary Cause."

The result of his investigation into spiritualistic manifestations led him to believe in the genuineness of their spiritual origin, and he embodied them in his book "Miracles and Modern Spiritualism." If his political works produced feelings of regret amongst many of his

scientific friends, his advocacy of spiritualism caused them (as Tyndall said) "feelings of deep disappointment." He was not, however, without able supporters in his "heresy," amongst them being Sir W. Crookes, Sir William Barrett, Lord Lindsay, Robert Chambers, and others.

Through his spiritualistic experience—of the actuality of which he was entirely convinced— he deduced a system of spiritual media, an angelology whereby the vast Divine Mind operates upon and communicates with "every cell of every living thing that is, or ever has been, upon the earth … through many descending grades of intelligence and power." He makes therefore his own, that which is, in effect, a summary of his teaching:—

"All nature is but art, unknown to thee,

All chance, direction which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony not understood;

All partial evil, universal good."

And therein he stands to-day the Grand Old Man of British Science, a true Revealer and Prophet, in the real sense of being a forthteller of the truth spoken to him.

Dr. Wallace has written many articles and smaller books on diverse subjects, the latest, which has aroused deep and widespread interest, being his "Social Environment and Moral Progress," which was written in his ninety-first year. In it he shows that there is no evidence

of any advancement in man's intellectual or ethical manifestation during the whole historical period, and he states his belief that no real improvement is possible until we reorganise society on a rational basis of mutual help, instead of our present system of mutual antagonism and degrading competition.

As has been well said—in a review of this work:—

"The author's position as co-discoverer with Darwin of one of the most momentous theories in the history of thought, his venerable age, his wide scientific knowledge and deep philosophic insight, lend to his utterances an authority such as could be claimed by no living writer."

His indictment of the present social environment as the worst in history constitutes a challenge to civilisation, and demands the closest scrutiny of the most impartial minds. He shows that it is well established that the essential character of man—intellectual, emotional, and moral—is inherent in him from birth; that it is subject to great variation from individual to individual, and that its manifestations in conduct can be modified in a very high degree by the influence of public opinion and by education. These latter changes, however, are not hereditary, and it follows that no definite advance in morals can occur in any race unless there is some selective or segregative agency at work. He declares that history shows that the increase of

wealth and luxury has been distributed with gross injustice, no provision having been made for the overflow of these being utilised for the greater happiness and comfort of the producers, or the improvement of the condition of the struggling millions.

He finds the "selective agency" which is to work for the amelioration which he desires, in sexual selection, which will be the prerogative of woman; and therefore woman's position in the not distant future "will be far higher and more important than any which has been claimed for or by her in the past." When political and social rights are conceded to her on equality with men, her free choice in marriage, no longer influenced by economic and social considerations, will guide the future moral progress of the race, restore the lost equality of opportunity to every child born in our country, and secure the balance between the sexes. "It will be their (women's) special duty so to mould public opinion, through home training and social influence, as to render the women of the future the regenerators of the entire human race."

But before this can effectively operate much has to be faced, and Dr. Wallace summarises the matter into one general conclusion, namely, that a civilised government must, as its prime duty, "organise the labour of the whole community for the equal good of all," but it is also bound immediately to take steps to "abolish

death by starvation and by preventable disease due to insanitary dwellings and dangerous employments, while carefully elaborating the permanent remedy for want in the midst of wealth." The laws of evolution are all in favour of such a revolution, but the present system of competition must become one of brotherly co-operation and co-ordination for the equal good of all. Apart from this there is no hope for advance towards true, living freedom, and this present volume on "The Revolt of Democracy" emphasises and illustrates this tremendous indictment.

And now we must bring to a close this very imperfect sketch, in the writing of which we have received great assistance, which we gratefully acknowledge, from Dr. Wallace himself, his son, Mr. W. G. Wallace, and a generous friend who desires to remain unknown.

In 1889 Dr. Wallace removed to Parkstone, Dorset, where he resided till 1902, when he again built himself a house—this time at Broadstone, overlooking Poole Harbour and the Purbeck Hills. Here he still lives and finds real interest and delight in his greenhouse and garden, Which have always been such a pleasurable source of recreation in his times of leisure.

He has always been an omnivorous reader, and his mind is stored with facts in relation to a very wide range of knowledge, while he is seldom without a novel by his side for his hours of relaxation.

Dr. Russel Wallace's Home at Broadstone, Dorset

Dr. Wallace's optimism is one of his most striking traits, and he looks back upon whatever misfortunes and hardships have fallen to his lot as blessings in disguise, which have strengthened his character and stimulated him to fresh endeavour.

At the memorable meeting of the British Association at Cambridge, in 1894, Lord Salisbury, recalling the historic reception of the Darwinian hypothesis in the same place half a century previously, and in paying a just tribute to Charles Darwin, said that "The equity of his judgment, the single-minded love of truth, and patient devotion to the pursuit of it through years of toil and of other conditions the most unpropitious—these things endeared to numbers of men everything that came from Charles Darwin, apart from his scientific merit and literary charm; and whatever final value may be assigned to his doctrine, nothing can ever detract from the lustre shed upon it by the wealth of his knowledge and the infinite ingenuity of his resource."

This tribute might be, with equal justice, applied to Wallace. In his charming modesty, his unselfishness, his instinct for truth—which, said Darwin to Henslow, "was something of the same nature as the instinct for virtue"—in his constant and singularly patient consideration of every opinion which differed from his own, and in his inventive imagination, Wallace is the worthy companion of Darwin.

But, as we have seen, he has other claims to be remembered by posterity. He is also a fearless social reformer who vigorously lays the axe to the root of great evils which flourish in our midst, some of which present-day society cherishes. He has struck what he believes to be a hard blow at vaccination—still an almost heaven-sent weapon against smallpox in the armoury of many doctors; and he has dared boldly to accept a spiritualistic interpretation of Nature, which is still treated as charlatanism.

He has not been the recluse calmly spinning theories from a bewildering chaos of observations, and building up isolated facts into the unity of a great and illuminating conception in the silence and solitude of his library, unmindful of the great world of sin and sorrow without. He could say with Darwin, "I was born a naturalist," but we can also add, his heart is on fire with love for the toiling masses. He has felt the intense joy of discovering a vast and splendid generalisation, which not only worked a complete revolution in biological science, but has also illuminated the vast field of human knowledge. Yet his greatest ambition has been to improve the cruel conditions under which thousands of his fellowcreatures suffer and die, and to make their lives sweeter and happier. His mind is great enough to encompass all that lies between the visible horizons of human thought and activity, and

now in his old age he lives upon the topmost peaks, eagerly looking for the horizon beyond. In the words of the late Mr. Gladstone's own precept, "He has been inspired with the belief that life is a great and noble calling, not a mean and grovelling thing that we are to shuffle through as we can, but an elevated and lofty destiny."

JAMES MARCHANT.

THE REVOLT OF DEMOCRACY

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

As President of the Land Nationalisation Society for thirty years, I have given much attention to the various inquiries by Royal Commissions, by Parliamentary Committees, or by private philanthropists, into Irish evictions and Highland clearances, sweating, unemployment, low wages, unhealthy trades, bad and overcrowded dwellings, and the depopulation of the rural districts. These inquiries have succeeded each other in a melancholy procession during the last sixty years; they have made known the almost incredible conditions of life of great numbers of our workers;

D

I

and they have suggested more or less ineffective remedies, but their proposals have been followed by even less effective legislation when any palliative has been attempted.

During the whole of the nineteenth century there was a continuous advance in the application of scientific discovery to the arts, and especially in the invention and application of labour-saving machinery; and our wealth has increased to an equally marvellous extent. Various estimates which have been made of the increase in our wealth-producing power show that, roughly speaking, the use of mechanical power has increased more than a hundredfold during the century; yet the result has been to create a limited upper class, living in unexampled luxury, while about one-fourth of our whole population exists in a state of fluctuating penury, often sinking below what has been termed

"the margin of poverty." Of these, many thousands are annually drawn into the gulf of absolute destitution, dying either from direct starvation, or from diseases produced by their employment, and rendered fatal by want of the necessaries and comforts of a healthy existence.

But during this long period, while wealth and want were alike increasing side by side, public opinion was not sufficiently educated to permit of any effectual remedy being applied for the extirpation of this terrible social disease. The workers themselves had not visualised its fundamental causes—land monopoly and the competitive system of industry, giving rise to an ever-increasing private capitalism which, to a very large extent, controlled the legislature. This rapid growth of wealth through the increase of the various kinds of manufacturing industry led to a still greater increase of middlemen engaged in the distribution of

its products, from wealthy merchants, through various grades of tradesmen and petty shopkeepers who supplied the daily wants of the whole community. To these must be added the innumerable parasites of the ever-increasing wealthy classes; the builders of their mansions and their factories; the makers of their furniture and clothing, of their costly ornaments and their children's toys; the vast body of their immediate dependents, from their managers, their agents, commercial travellers and clerks, through various grades of domestic servants, grooms and gamekeepers, butlers and housekeepers, down to stable-boys and kitchen-maids, all deriving their means of existence from the wealth daily produced in mines, factories and workshops. This was apparently due primarily, if not exclusively, to the capitalists themselves as the employers of labour, without whose agency and super-

vision it was believed that all productive labour would cease, bringing ruin and starvation to the whole population. Thus, a vast mass of public opinion was created, all in favour of the capitalists as the employers of labour and the true source of the creation of wealth.

To those who lived in the midst of this vast industrial system, or were a part of it, it seemed natural and inevitable that there should be rich and poor; and this belief was enforced on the one hand by the clergy, and on the other by the political economists, so that religion and science agreed in upholding the competitive and capitalistic system of society as being the only rational and possible one. Hence, till quite recently, it was believed that the abolition of poverty was entirely outside the true sphere of governmental action. It was, in fact, openly declared and believed that poverty was due to

economic causes over which governments had no power; that wages were kept down by the "iron law" of supply and demand; and that any attempts to find a remedy by Acts of Parliament only aggravated the disease. This was the doctrine held, even by such great men as W. E. Gladstone and Sir William Harcourt, together with the dogma that it was a government's duty to buy in the cheapest market, in order to protect the taxpayer. It was the doctrine also which converted the misnamed "guardians" of the poor into guardians of the ratepayers' interests, and led to that rigid and unsympathetic treatment of the very poor which made the workhouse more dreaded than the jail, and which to this very day leads many of the most destitute to die of lingering starvation, or to commit suicide, rather than apply for relief or enter the gloomy portals of the workhouse.

CHAPTER II

THE DAWN OF A NEW ERA

IT was, I believe, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, when he became Prime Minister in 1905, who changed this attitude of negation of all his predecessors. He boldly declared in numerous speeches, both in and out of Parliament, that he held it to be the duty of a government to deal with the great problems of unemployment and poverty, and especially to attack the increasingly injurious landmonopoly, and so to legislate as to make our native soil ever more and more "a treasure-house for the poor rather than a mere pleasure-house for the rich." And as an earnest of his determination to carry out these views, he brought into his

Ministry John Burns and David Lloyd George, the former for his knowledge of the conditions and aspirations of skilled labour, and his administrative experience both in the County Council and in Parliament, and the latter for his energy as an advanced thinker, his powers of public speaking, and his enthusiasm for social reform.

When Mr. Asquith became Prime Minister in 1908, he made Mr. Lloyd George his successor as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and never was the wisdom of an appointment more fully justified. The new Chancellor, in the memorable Budget thrown out by the House of Lords, made provision not only for our ever-increasing Navy, but also for Old-Age Pensions and for far-reaching measures calculated to benefit the working classes.

It is, in my opinion, largely due to this attitude of Liberal Governments, without

adequate remedial legislation, during the last seven years, with a corresponding change in public opinion, that has led to the recent effort of the workers to bring about better conditions by means of combined strikes. The three great strikes in rapid succession, of the Railway and other transport Unions, of the Miners, and of the London Dock Labourers, must have brought home to the middle and upper classes and to the Government how completely they are all dependent on the often despised working classes, not only for every comfort and luxury which they enjoy, for the means of rapid locomotion and of carrying on their respective businesses and pleasures, but also for obtaining the daily food essential for life itself. The experience now gained shows us that when the organisation of the trade unions is rendered more complete, and the accumulated funds of a dozen or twenty years

are devoted to this one purpose, the bulk of the inhabitants of London, or of any other of our great cities, could be made to suffer a degree of famine comparable with that of Paris when besieged by the German army in 1870.

It is to be hoped that such a disaster will not happen, but it can only be prevented by much more effective action than has yet been taken to improve the social status of the great body of industrial and other workers, and to abolish completely the conditions which compel a large proportion of those workers to exist on or below the margin of poverty, often culminating in actual death from want of the bare necessaries of existence.

CHAPTER III

THE LESSON OF THE STRIKES

THE serious position which these successive strikes have brought about has led to much discussion in the newspapers and other periodicals, in which a number of wellknown literary men have taken part, and, what is much more important, in which several of the most able and intelligent of the workers themselves have clearly stated their determination to obtain certain fundamental reforms. Month by month it has become more clear and certain that what has been termed "The Labour Unrest" will certainly continue with ever-increasing determination and effective power till some such reforms as they demand are conceded by the Government.

A careful study of the more important of these various pronouncements shows us that two things stand out clearly, as to which there is almost universal agreement. These are, first, that the condition of the workers as a whole is absolutely unbearable, is a disgrace to civilisation, and fully justifies the most extreme demands of the workers; and, secondly, that among the whole of the writers—whether statesmen or thinkers, capitalists or workmen—there is not one who has proposed any definite and workable plan by which the desired change of conditions will be brought about. Yet one such plan was carefully worked out more than twenty years ago, and though the book had a considerable sale and a cheap edition of it was issued, not the slightest effect was produced on public opinion or on the Government.* The time had not yet come for such radical reforms

* See Rev. H. V. Mills' Poverty and the State.

to be seriously considered. But conditions have changed, and some definite action is now imperatively demanded if this "unrest" is to cease, and if the reasonable claims of the workers are to be satisfied. Let us see, then, what these claims are, and why none of the various palliatives hinted at by a few of those who have taken part in the discussion can do any real good, while they will certainly not satisfy the workers or allay their quite justifiable "unrest."

CHAPTER IV

WHAT THE WORKERS CLAIM AND MUST HAVE

THE workers' claim is put forward by Mr. Vernon Hartshorn in the following clear and terse statement:

"What is that demand? It is, that the community shall guarantee to the men and women who perform services essential to the existence or happiness of the community, a reasonably comfortable and civilised livelihood—a decent minimum of food and clothing, leisure and recreation, and houses fit for human beings."

Then he proceeds to ask:

"How do the workers propose that the community shall give them that guarantee? By the establishment of a legally guaranteed eight-hours day. By the establishment of a national housing standard at a rent within the reach of the workers.

And also by the power of the trade unions to check the exploitation of Labour by competitive methods which tend to force down the average standard of living among the working classes."

Then, after a reference to the recent claim of the doctors to what they consider a living wage under the National Insurance Act, and also to the many luxuries of the rich which the workers do not want, he again states the workers' claim thus:

"It is not an extravagant demand. It is just the plain blunt demand that might be expected from British working-men. … It is a demand by those who, either by hand or brain, make the wealth of the nation, that the first charge upon that wealth shall be the maintenance of themselves in reasonable comfort."

Then he concludes with this important declaration of policy:—

"Democracy must be its own emancipator; But institutions like the Church, Parliament, and the Press, and even the rich, have to make up their minds

as to what shall be their attitude toward it. They must decide for themselves whether the demand of the workers for a fairer share of the good things of life is just or unjust. The working classes have already made up their minds. They are convinced that their demand is just, and with a highly intelligent, vigorous working class, stung by a sense of injustice, the future of this country will be full of danger. The stupid attitude of hostility or superior patronage which has been adopted towards the working classes in the past by powerful elements in society has helped to generate the present revolutionary upheaval. … The worker does not want charity to redress the balance. He knows that charity robs him of his manhood. He feels that he is entitled to a man's share of the wealth he has produced, and he wants it assured to him, not as a charity, but as a citizen's right."

Then, after describing how neither Parliament nor the present Government can or will secure this for him, and that their methods of "conciliation" or "arbitration" are useless or inadequate, he concludes:

"There is only one way to industrial peace. There is only one way to stave off a class war which may shake civilisation to its foundations. It is by a full and frank acknowledgement by society that the claim of the worker to a sufficiency of food and clothing and a fuller life is just, and that it must be made the first charge upon the wealth produced. … It is the present order of society which is upon its trial. Can it do justice to the worker? If it can, and if it does, then it will have justified its existence. But if it cannot, then its ultimate doom is sealed."

Quotations from other Labour leaders could be made to the same effect, showing that the workers now know their rights and are determined to obtain them. But they do not see exactly how that is to be done, and it is for their friends and well-wishers to assist them in finding out a way.

A few useful indications of how we must approach the problem may be quoted.

Mr. Seebohm Rowntree, one of the

E

best and most sympathetic employers of labour in the country, tells us that—

"The capitalists should entirely shake off the idea that wage-earners are inferior beings to themselves, and should learn to regard them as valued and necessary partners in the great work of wealth-production—partners with whose accredited representatives they may honourably discuss the proportions in which the wealth jointly produced should be divided."

He also sees clearly, and declares that—

"The poverty at one end of the social scale will not be removed except by encroaching heavily upon the great riches at the other end."

But this, apparently, is the last thing capitalist employers want or will submit to.

Mr. Frederic Harrison urges that labour cannot be in a settled and healthy state

"till seven hours is made the normal standard of a day's labour,"

and that—

"a fixed living wage is merely the irreducible part of the remuneration, the rest being proportioned to the profits on the work done."

And he concludes his most interesting and suggestive article with the dictum that—

"The unrest is come to stay, and will not be ended by petty devices."

Mr. Sidney Low tells us that there are many young men among the workers who read Carlyle and Ruskin, and believe that if our society were rightly organised the life of cultivated leisure would not be the privilege of the Few, but the possession of the Many. Mr. Geoffrey Drage confirms this statement, and declares that—

"the worker sees that the time for cries is past, the time for action is come."

But he, too, like all the others, gives

no clue as to how the great change is to be brought about, not sporadically here and there, but universally—not by slightly improving the condition of skilled labour only, but by such means as will immediately begin to act upon the lowest stratum of the social fabric, and in a measurable space of time abolish want, culminating in actual starvation, in this land of ever-increasing wealth, and ever more and more extravagant luxury.

Before laying before my readers what I conceive to be, at the present juncture, the best and, indeed, the only mode of successfully attacking this great and pressing problem, I will give the statement of Mr. Anderson, the Chairman of the Conference of the Independent Labour Party, in the autumn of 1912. In reply to a Press representative, he said:

"The whole upheaval is a revolt against poverty; against, that is, Social Injustice; and it involves

the Right to Live … Strikes are disintegrating. they are no real and permanent remedy. We have to find the solution in some new basis for industrial reform, and my view is, that if reform is to do any good it must contain in itself the germ of a better social organisation. Palliatives are no cure."

And then, when he was urged to say, "What do you actually propose?" his reply was:

"We are determined that destitution must be stamped out; and our remedy resolves itself into this: A national minimum of Wages, Housing, Leisure, and Education. That is Labour's battle-cry for the future."

CHAPTER V

A GOVERNMENT'S DUTY

Now, in all the foregoing views of the leaders and the friends of Labour, there is a very close agreement as to the present position of the whole body of workers, and as to the nature and amount of the reforms they insist upon, without which they will not be satisfied, and will not cease from agitation, culminating in more extensive and more determined and better-organised strikes. This will be the only method left open to them if their admittedly moderate and just claims are not fully and honestly recognised by the party in power, and at once translated into adequate direct action.

It is a very strange thing to me, and

must be so to many others, that in this most wealthy country a powerful Government, long pledged to social reform, cannot or will not take any immediate and direct steps to abolish the pitiable extremes of destitution which are ever present in all its great cities, its towns, and even its villages! The old, complex and harsh machinery of its Poor Laws has become less and less efficient. Enormous sums spent in various forms of charity do not prevent starvation, do not appear to diminish it. The cause of this almost universal apathy is the very persistence of destitution and its obscurity. The various forms of charity are more conspicuous and more obtrusive, so that most people are quite unable to realise that starvation is still rampant to a most terrible and most disgraceful extent all over our land.

In 1898 I published in my volume on The Wonderful Century an appendix on

"The Remedy for Want in the Midst of Wealth," but, thinking that the general scheme I proposed was too advanced for immediate adoption, I also gave a plan, headed "How to Stop Starvation," which began with these words:

"But till some such method is demanded by public opinion, and its adoption forced upon our legislators, the horrible scandal and crime of men, women, and little children, by thousands and millions, living in the most wretched want, dying of actual starvation, or driven to suicide by the dread of it, must be stopped!"

The Chairman of the Independent Labour Party now also declares that "Destitution must be stamped out."

Since the above passage was written nothing effective has been done; the horrors of our slums are as bad as ever, our cumbrous and unsympathetic systems of poor relief are utter failures. I, therefore, again submit my simple and

practical suggestion, which is as much needed to-day as it was then. It is as follows:

"The only certain way to abolish starvation, not when it is too late, but in its very earliest stages, is free bread. I imagine the outcry against this: 'Fraud! Loafing! Pauperisation!' etc., etc. Perhaps so; perhaps not. But even if it must be so, better give bread to a hundred loafers than refuse it to a hundred who are starving. All who want it, all who have not money enough to buy wholesome food and other necessaries, must be able to get this bread with the minimum of trouble. There must be no tests like those for Poor Law relief. A decent home, with good furniture and good clothes, must be no bar; neither must the possession of money if that money is needed for rent, for coals, or for other absolute necessaries of life. The bread must be given to prevent injurious destitution, not merely to alleviate it. The bread is not to be charity, not poor relief, but a rightful claim upon society for its neglect to organise itself so that all, without exception, who have worked, and are willing to work, or are unable to work, may at the very least have food to support life.

"Now for the mode of obtaining this bread. All local authorities shall be required to prepare bread-tickets duly stamped and numbered with coupons to be detached, each representing a 2-lb. or 4-lb. loaf. These tickets to be issued in suitable quantities to every policeman, to all the clergy of every denomination, and to all medical men. Any person in want of food, by applying to any of these distributors is to be given a coupon for one loaf, without any question whatever.

"If the person wants more than one loaf, or wishes to have one or more such loaves for a week, a name and address must be given. The distributor, or some deputy, will then pay a visit during the day, ascertain the bare facts, give a suitable number of tickets, and, as in cases of sickness or of young children, obtain such other relief as may be needed."

The cost of dealing with this widespread destitution should be borne by the National Exchequer, both because it is due to deep-seated causes in our social economy, and also because its distribution is very unequal, so that the cost would

be heaviest in the poorer and lightest in the richer areas. It must, however, be treated as essentially of a temporary nature, only needed till the fundamental causes of poverty are properly dealt with by some such method as that to be explained later on, when any such expedient will become a thing of the past.

When we consider that during the last fourteen years our national expenditure has increased by about £80,000,000, and that it has now reached the vast amount of £185,000,000, it is almost incredible that we should have made no serious attempt to discover the causes and apply the remedy to this terrible social canker in our civilisation. Now, however, that the Labour Party insists upon an immediate remedy being applied, and also claims for the sufferers and for the whole body of workers full social equality with all other citizens—a claim recognised by many

of our best and greatest writers to be a just one—perennial starvation of our very poor must no longer be ignored, and our Government must grapple with it without further delay.

Government and its Employees

We will now proceed to consider how the Government can itself lead the way towards that new organisation of society which will afford a permanent remedy for labour unrest, and satisfy the just demands of some considerable portion of the workers of our country.

The Prime Minister has quite recently declared his invincible objection to fixing even a minimum wage by Act of Parliament, but no positive objection has been made to raising the wages of all Government employees above such a minimum. This has been asked for again and again by the workers themselves, as well as by their representatives in Parliament, but

has only been acted upon partially, and any proposal for giving higher wages than are paid by private capitalists has been objected to for various reasons. It is said to be unfair to thus compete with private enterprise; that more men at present wages can always be had than are required; and other reasons of the usual type of the old school of economists. These objections are also upheld for political reasons, since the large number of capitalists and wealthy employers of labour in the House of Commons would violently oppose any such unprecedented expenditure, and endanger the very existence of the Government.

But all these objections may now, perhaps, be much weakened, or even disregarded, in view of the recent strikes and the future possibilities they suggest. The workers are now steadily becoming better organised and more conscious of their own