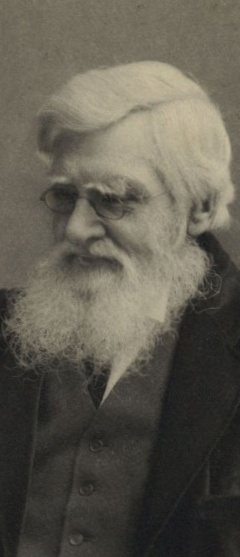

Alfred Russel Wallace. A biographical sketch

by John van Wyhe

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) was a great English naturalist who is primarily remembered for conceiving of a theory of evolution by natural selection independently of Charles Darwin. Unlike Darwin, Wallace came from a rather humble and ordinary background. His English father, a solicitor by training, once had property sufficient to generate a gentleman's income of £500 per annum. But financial circumstances declined so the family moved from London to a village near Usk, on the Welsh borders, where Wallace was born in the large Kensington Cottage on 8 January 1823. The son of a gentleman, Wallace was middle class.

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) was a great English naturalist who is primarily remembered for conceiving of a theory of evolution by natural selection independently of Charles Darwin. Unlike Darwin, Wallace came from a rather humble and ordinary background. His English father, a solicitor by training, once had property sufficient to generate a gentleman's income of £500 per annum. But financial circumstances declined so the family moved from London to a village near Usk, on the Welsh borders, where Wallace was born in the large Kensington Cottage on 8 January 1823. The son of a gentleman, Wallace was middle class.

When Wallace was about six years old the family moved to Hertford, north of London, where he lived until he was fourteen. Here Wallace attended Hertford Free Grammar School which advertised itself as a school for the sons of gentlemen, and offered a classical education, essentially identical to Darwin's at Shrewsbury Free Grammar School, including Latin grammar, classical geography and "some Euclid and algebra". Wallace left school aged fourteen in March 1837, shortly after Darwin returned from the Beagle voyage. Wallace was not forced to leave school early because of financial difficulties, as frequently claimed in recent years, but finished school at the normal age. This view probably arose from Wallace's touching recollections of the embarrassment he felt as his family's lack of money became obvious to his fellow students and because almost all modern writers on Wallace are not qualified historians of the period. Wallace never attended university like almost everyone else at the time. Rather than emphasizing his lack of a university degree, the important point that for this time in history, Wallace was well educated.

Wallace then left home to join his elder brother John, an apprentice builder in London. Wallace spent his evenings in an educational "Hall of science" for working men. Here Wallace saw working-class people up close, but saw them as different from himself. In this context (according to his later recollections) Wallace encountered the socialist ideas of the reformer Robert Owen although the influence of such ideas only seem to appear in his later life. Wallace would eventually be deeply impressed by Owen's utopian social ideals - with a stress on the role of environment in determining character and behaviour. Hence, if the social environment were improved, so would the morals and well being of the workers. The hall of science also introduced Wallace to the latest views of religious sceptics and secularists. Although Wallace's parents were perfectly orthodox members of the Church of England, Wallace became a sceptic or freethinker. However we have very little evidence about this.

From 1837 Wallace joined his brother William to work as an apprentice land surveyor. Here in Wallace Online you can see, for the first time, some of the original maps he contributed to click here. Wallace began to read about mechanics and optics, his first introduction to science. His days surveying in the open air of the countryside lead him to an interest in natural history. From 1841 Wallace took up an amateur pursuit of botany by collecting plants and flowers. We now know that Charles Darwin had already come up with his theory of evolution by natural selection by this time.

Survey map of the parish of Neath (1845). Courtesy of the National Library of Wales.

From 1840-1843 Wallace remained employed as a surveyor in the west of England and Wales. In 1843 his father died. With a decline in the demand for surveyors William no longer had sufficient work to employ Wallace. After a brief period of unemployment in early 1844 Wallace worked for over a year as a teacher at the Collegiate School at Leicester. Obviously he would not have been qualified to be a teacher if he had not completed his schooling.

Reading

In these years Wallace read some very influential works for his future life. Alexander von Humboldt's Personal narrative (1814-1829) and Darwin's Journal of researches (1839) introduced Wallace to the exciting allure of scientific travel and collecting. Another major influence on Wallace was Charles Lyell's Principles of geology (1830-3). He also read Thomas Malthus's Essay on the principle of population (1826). All of these works are provided as supplementary works in Wallace Online.

Wallace also read the hugely controversial and anonymous popular science book Vestiges of the natural history of creation in 1845. Vestiges argued for the progressive physical "development" (evolution) of all of nature from solar systems to the Earth and biological species, in a progressive, upward direction. Much of the naturalistic philosophy of Vestiges was derived from a work Wallace had already read, the phrenologist George Combe's Constitution of man (1828). Both works described nature as governed by universal and beneficent natural laws tending towards progress. These were extremely popular themes of the day.

These, together with Darwin's numerous remarks hinting that species change and Lyell's lengthy criticisms of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's evolutionary theory, despite a masterful overview of the evidence for "the gradual birth and death of species", all contributed to Wallace privately accepting the view that species were not fixed and permanent creations but could change over time.

At the Leicester library, no doubt reading some of these books, Wallace met another budding young naturalist, an enthusiastic entomologist named Henry Walter Bates. Bates, who had finished school at the same age, introduced Wallace to his next scientific pursuit and, indeed, passion: collecting insects, particularly beetles. Wallace was amazed at the incredible diversity of beetles that could be collected around Leicester. Wallace's first scientific publication was, like Darwin's, the record of an insect capture.

Wallace's eldest brother William died in March 1845, causing Wallace to leave the Leicester school to attend to William's surveying firm in Neath, together with his brother John. Wallace next worked as a surveyor for a proposed rail line for a few months. Then he and John attempted to establish an architectural firm which produced a few successful projects such as the building for the Mechanics' Institute of Neath which happily still survives. The director of the Mechanics' Institute invited Wallace to give some lectures there on science and engineering. Clearly science was already Wallace's primary interest and he had local a reputation as a knowledgeable person.

Wallace's eldest brother William died in March 1845, causing Wallace to leave the Leicester school to attend to William's surveying firm in Neath, together with his brother John. Wallace next worked as a surveyor for a proposed rail line for a few months. Then he and John attempted to establish an architectural firm which produced a few successful projects such as the building for the Mechanics' Institute of Neath which happily still survives. The director of the Mechanics' Institute invited Wallace to give some lectures there on science and engineering. Clearly science was already Wallace's primary interest and he had local a reputation as a knowledgeable person.

The Amazon, 1848-1852

Wallace and Bates were inspired by a recent book by American traveller William Edwards: A voyage up the river Amazon, including a residence at Para. They estimated that by collecting natural history specimens such as insects and birds and selling them to museums, they could support themselves and indeed earn substantial profits from an overseas expedition. It has become increasingly fashionable to claim that they went to the Amazon to "solve the problem of the origin of species". This heroically romantic story is also recent and not correct as has been demonstrated here. Both at that time and for the rest of his life, Wallace always described the trip as one to be a collector. The entire notion of Wallace and Bates setting out to solve some great scientific problem of the day is an anachronism as such thinking (and even the phrase "problem of the origin of species") only emerged after the publication of Darwin's On the origin of species in 1859.

In April of 1848 Wallace and Bates sailed for Brazil. They initially stayed in Para (now Belém). After nine months collecting Amazonian specimens together Wallace and Bates continued separately. Wallace focused particularly on collecting in and exploring the Upper Rio Negro. One of the main scientific results of Wallace's time on the Amazon was an appreciation of biogeographical boundaries, particularly broad rivers, that he found separated different species or varieties he was collecting. Such factors were still under appreciated at the time.

In 1852 Wallace prepared to return home. According to his later account he had to publish an announcement of his intention to leave in a local newspaper- one of his rare publications that has yet to be tracked down. After he set sail for Britain disaster struck when the ship caught fire and sank in the Atlantic, destroying almost the entirety of his notes and personal collection. Fortunately, Wallace and the others on board were rescued and his collection had been insured by his London agent Samuel Stevens for £200.

Wallace's subsequent publications suffered from the dearth of data he was able to bring home. His first book, Palm trees (1853), described the distribution and local uses of the palms he had observed and was illustrated with his sketches saved from the doomed ship. His other book was the usual sort of scientific travel diary: A narrative of travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro (1853). Wallace also read papers before scientific societies and made important connections in the London scientific community. All of these activities helped raise Wallace's profile enough to seek the patronage of the elite and apply for financial assistance to set out on another collecting expedition.

Southeast Asia 1854-1862

Route of Wallace's travels from The Malay Archipelago (1869).

After only eighteen months back in England, Wallace again set off for the tropics to work as a specimen collector. As Bates and others remained in the Amazon basin, Wallace headed instead for Southeast Asia, then sometimes called the Malay Archipelago. He was advised that British cabinets were particularly lacking in specimens from those regions and hence it would be profitable collecting ground. The scientific connections made during his time in London secured him government funding which paid for a very expensive first-class passage to Singapore for Wallace and a teenage assistant named Charles Allen. They arrived in Singapore in April 1854. See Wallace in Singapore

Over the next eight years Wallace and an ever changing team of local assistants made dozens of expeditions and amassed a massive collection of 125,000 specimens of insects, birds and mammals. His time in the East was, in his own words, "the central and controlling incident of my life". Hundreds of these specimens can now be seen for the first time in the collection of contemporary scientific descriptions of Wallace's collections in Wallace Online. See Specimens

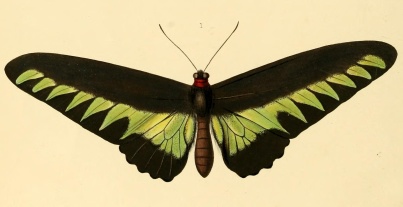

Wallace discovered hundreds and indeed probably thousands of new species including the world's largest bee and rarest cat. (below) His Malay assistant Ali from Sarawak shot a new species of bird of paradise now known as Wallace's Standard Wing. See here. In October 1858 Wallace prepared a brief note 'Direction for Collecting in the Tropics' for other collectors which gives some insights into his career as a collector.

|

Wallace named this butterfly after Sir James Brooke. Ornithoptera brookiana (now Trogonoptera brookiana). |

Evolution in the archipelago

In 1855, while living in the province of Sarawak on the great island of Borneo, Wallace was annoyed by a recent article by the naturalist Edward Forbes, newly appointed Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh. Amongst other things, Forbes argued that the fossil record gave no support to the various theories of evolution that had so far been suggested.

In reaction Wallace wrote his first theoretical paper on species: 'On the law which has regulated the introduction of new species'. Wallace argued that the fossil record was not so random as Forbes suggested and that "Every species has come into existence coincident both in time and space with a pre-existing closely allied species". Although a lucid analysis of the paleaontological and biogeographical evidence of the time, the paper did not state that species change or evolve. This is a universal misunderstanding of the paper. Instead, Wallace, as he later wrote, left this point to be "inferred". Most modern readers, however, mistakenly assume that the essay openly declared a belief in evolution. Indeed, Wallace many times referred in the paper to new species being "created". This was not language that he used in his private notebooks. Clearly he was not ready to expose his unorthodox beliefs which could have seriously damaged his reputation and hurt his future job prospects. See a historical (as opposed to a modern popular science/amateur) explanation of the original meaning of the paper here.

Wallace continued reading about the history of life and jotting notes about how he believed species changed. But he was certainly not, as modern popular writers tend to romantically put it, on the search for the 'mechanism' for how species evolve. As he collected more and more specimens and observed the change of animals from island to island, his ideas about life also evolved. He was convinced that species must be related genealogically- not just somehow created to suit their environments. Indeed, he argued in an 1856 paper 'On the habits of the Orang-utan of Borneo' that one should not seek for reasons why all structures of living things were adaptive. This is not the thinking of one seeking a 'mechanism' for biological adaptation or evolution. Wallace's thinking was still evolving.

Six month's before his dramatic eureka moment, Wallace wrote an unusually turgid article: 'Note on the theory of permanent and geographical varieties'. In this often misunderstood piece Wallace pointed out inconsistencies with "independent creations" of species and hinted for the first time in print at genealogical descent as the more plausible origin of new species, all the way appearing a neutral and objective observer. (See also S58.)

In February 1858 Wallace was living on the island of Ternate in the Moluccas, the fabled spice islands, west of New Guinea, and then part of the Dutch East Indies. According to his later recollections, he was suffering from a recurring bout of fever when he suddenly conceived of an explanation for the origin of new species through a struggle for existence.

In February 1858 Wallace was living on the island of Ternate in the Moluccas, the fabled spice islands, west of New Guinea, and then part of the Dutch East Indies. According to his later recollections, he was suffering from a recurring bout of fever when he suddenly conceived of an explanation for the origin of new species through a struggle for existence.

For many years it has been claimed that Wallace was actually on the nearby island of Gilolo (Halmahera) when this happened. This has now been proven incorrect. Wallace was actually on Ternate, as he signed his essay. He always signed documents from his actual location and never signed them instead, as has been often suggested, as from a postal base.

Years before he had read Thomas Malthus's observations that inevitable geometrical population growth was prevented only by severe checks. Although Wallace later wrote that he thought of Malthus at the time of his revelation, we cannot be sure of this. Wallace's essay does not mention Malthus. Nor did Malthus's name came up in his writings until after Wallace had read Darwin and his mention of Malthus. It is perfectly possible that Wallace did think of Malthus at the time, but since the only evidence is his much later recollection and there is nothing specific to the writings of Malthus in his 1858 writings, we must remain agnostic on the point.

The point that certainly did occur to Wallace (and could by then be found in the writings of many authors) was that many are born and few survive. Indeed the 'struggle for existence' was well described in a book we know he had next to him at the time, the 4th edition of Lyell's Principles of Geology. Wallace's essay was written primarily against Lyell's anti-evolutionary views that species could not depart (change) very far from their original type. Wallace conceived of "a general principle in nature" that permitted only a "superior" minority variety to survive "a struggle for existence". This could explain how organisms became naturally adapted to their environments. How, for example, does an insect perfectly match the colour of its background? Because, he explained, many differently coloured varieties of a parent species frequently appear. If the environment were to gradually change colour, as so well described by Lyell, a parent species might no longer match it and become unsuited but one of its daughter varieties might happen to already by the colour of the new environment. This new variety would then replace the parent species. The variety could not revert, as Lyell had insisted, back to the parental form, because that was now inferior in the new environment. And thus, if this process were reiterated, varieties would come to diverge ever further from the form or type of the original parent species.

Wallace elaborated his new theory in an essay entitled 'On the tendency of varieties to depart indefinitely from the original type'. It was one of the most original and brilliant scientific essays ever written and demonstrates Wallace's independent formulation of a form of what Darwin called "natural selection". The essay is heavily influenced by Wallace's study of Lyell's Principles of geology. Today it is all too easy to read the essay with modern eyes and ideas and almost impossible to understand it historically in its original context. In Dispelling the Darkness (2013) readers can find the elusive and surprising original historical meanings of Wallace's important essay. Wallace's original theory was quite different from Darwin's.

Darwin vs. Wallace?

What happened next has been surrounded by confusion and conspiracy theories for decades. However, these have all been disproven in recent years. Darwin did not lie about when he received Wallace's essay, withhold it or borrow anything from it. The gradual formation of Darwin's ideas are well attested in his surviving notes and notebooks and these have been meticulously studied by scholars for many years. Qualified scholars all accept that Darwin did and could not have needed to borrow any of the ideas from Wallace's essay as Darwin had been working on his own theory for 20 years and worked out very many topics and aspects of it that Wallace had not had time to think of or address.

What happened next has been surrounded by confusion and conspiracy theories for decades. However, these have all been disproven in recent years. Darwin did not lie about when he received Wallace's essay, withhold it or borrow anything from it. The gradual formation of Darwin's ideas are well attested in his surviving notes and notebooks and these have been meticulously studied by scholars for many years. Qualified scholars all accept that Darwin did and could not have needed to borrow any of the ideas from Wallace's essay as Darwin had been working on his own theory for 20 years and worked out very many topics and aspects of it that Wallace had not had time to think of or address.

Unlike any other scientific paper he wrote in the East, Wallace did not send the essay for publication after he finished it in early February 1858. It was the first explicitly evolutionary writing he had ever prepared. However, shortly after writing it, on the monthly mail streamer of 9 March, Wallace received a letter from Darwin which contained high praise for the Sarawak Law paper and the news that the famous Sir Charles Lyell greatly admired the paper. Wallace was inspired. If the Sarawak paper had impressed the great Lyell, perhaps the new Ternate essay would impress him too. Perhaps Wallace could even convince Lyell that his own principles actually supported, rather than contradicted, evolution. The Ternate essay was written with Lyell in mind.

So Wallace, writing in the same unbroken sequence of letter receipt and reply that he and Darwin had been engaged in for some time- sent his essay to Darwin in reply and asked that if Darwin thought the essay was sufficiently interesting that he might forward it to Lyell. Wallace already knew from Darwin's letters that he was preparing a large work on evolution. Hence Darwin was the only prominent man of science that Wallace knew who would be sympathetic to this first explicitly evolutionary essay by Wallace.

But when did Wallace send the essay to Darwin? This was for many years considered to be a great unresolvable mystery and gave fuel to the conspiracies. The essay was dated Ternate, February 1858. Like almost all of Wallace's essays sent back to Britain, the original manuscript and covering letter do not survive. If the essay was sent to Darwin on the next monthly mail steamer after February, as Wallace's recollections over a decade later imply, this would have been 9 March 1858. A letter to Frederick Bates (brother of H. W. Bates) sent on this steamer still survives and bears postmarks showing that it arrived in London on 3 June. But Darwin's letter to Lyell, which mentioned receipt of Wallace's essay on the same day, was dated "18" June 1858.

So, several writers have asked, if both letters left Ternate on the same mail steamer (there was only one per month), how could Darwin receive his on 18 June and not 3 June? But there was never any evidence that Wallace sent both letters on the same day, it was simply a long-running assumption since McKinney in 1972. Receipt by Darwin on 18 June 1858 is exactly the right day for the mail steamer that left Ternate in April, through an unbroken series of mail steamer connections, as revealed by van Wyhe & Rookmaaker 2012 and Dispelling the Darkness pp. 225-6, 358 note 692. In fact, this date is exactly what one would expect for Wallace to reply to Darwin's letter that arrived on 9 March. Wallace is never known to have replied to a letter via the same Ternate mail same steamer on which that letter arrived. The turnaround time made that impossible. Furthermore, all commentators on this pseudoproblem ignored the fact that Darwin's mention of it arriving on the "18"th - being actual contemporary evidence - is worth vastly more than any later recollection by Wallace as to when he sent it.

A critic, with no historical training or qualifications, maintained that this reconstructed route had an interruption. This was in fact a bold assertion that the mail bags were thrown off the mail ship before it sailed on to the next postal connection, Singapore. An astonishing idea that mail bags would be slowed down and not continue on the same ship. Only historically untrained writers still consider such an assertion to be worth consideration or that the matter is still undecided.

It has since been demonstrated that this connection was not interrupted, because the latest newspaper from the Dutch East Indies was discussed in the Singapore newspapers immediately after the arrival of the steamer in question. Proving beyond doubt that the mails (which included Wallace's letter to Darwin) were on board from the Dutch East Indies. (Dispelling the Darkness p. 358 note 692.)

Darwin was by then about two years away from completing and publishing his big book on his species theory. Surprised by Wallace's essay, but very much the Victorian gentleman, Darwin at first proposed to send Wallace's essay for publication and give up his own twenty years' of priority in publishing. He forwarded it on to Lyell the same day. Concerned that their friend would lose his priority in the idea of natural selection, Lyell and especially Joseph Dalton Hooker had extracts from Darwin's manuscripts on species from 1844 and 1857 and Wallace's cleanly written essay read before the prestigious Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858. These documents were published together as a joint contribution in the Society's proceedings in August 1858. Thus began the long series of events that are usually called the Darwinian revolution.

Recent commentators make much of this so-called 'delicate arrangement' (as shown by John van Wyhe, this is in fact a misquotation). Many accusations have been made that this was not fair to Wallace, that his essay was published without his consent, that he was relegated to an inferior position or that Darwin overshadowed Wallace's contribution and that Darwin's subsequent fame is a result of this.

None of these are true and all of these ideas originated since the middle of the 20th century with writers with no historical qualifications, training and in most cases any competence in the history of science field. By sending his formally written or fair copy essay to Darwin and Lyell without marking it as private or not to be published, the convention of the day was, as Wallace well knew, that it could be published at the discretion of his recipients. This is why he expressed no surprise or disappointment when he learned that it had been. We can see how delighted he was that his paper had been so highly appreciated and fast-tracked into print by the letter he wrote to his mother as soon as he heard the news:

I now received letters informing me of the reception of the paper on "Varieties," which I had sent to Darwin, and in a letter home I thus refer to it: "I have received letters from Mr. Darwin and Dr. Hooker, two of the most eminent naturalists in England, which have highly gratified me. I sent Mr. Darwin an essay on a subject upon which he is now writing a great work. He showed it to Dr. Hooker and Sir Charles Lyell, who thought so highly of it that they had it read before the Linnean Society. This insures me the acquaintance of these eminent men on my return home." (My life 1: 365)

Many recent writers are very aggrieved by Wallace not having as much credit, fame or status as Darwin because the two men published natural selection simultaneously. While those without historical training may insist that in science, publication is everything when it comes to priority, that was not the case in the 19th century. Wallace himself, in thanking Hooker for his role in publicising Wallace's 1858 essay, noted that:

Allow me in the first place sincerely to thank yourself & Sir Charles Lyell for your kind offices on this occasion, & to assure you of the gratification afforded me both by the course you have pursued, & the favourable opinions of my essay which you have so kindly expressed. I cannot but consider myself a favoured party in this matter, because it has hitherto been too much the practice in cases of this sort to impute all the merit to the first discoverer of a new fact or a new theory, & little or none to any other party who may, quite independently, have arrived at the same result a few years or a few hours later. (van Wyhe & Rookmaaker, Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago, 2013, p. 181)

Wallace acknowledged that normally all the merit went to the first to discover, not the first to publish, and how favoured he felt that priority of publication in this case had been shared.

Wallace benefited from this joint presentation and publication with Darwin more than any other publication or arrangement in his life. Darwin's greater fame during the 19th century and today has nothing to do with the Linnean Society reading, the subsequent publication or the chronological arrangement of their contributions. No one was concerned at the time with such a petty matter. It stems solely from the monumental success of Darwin's epoch making book, On the origin of species.

Return to Britain

After Wallace's return to Britain in 1862 he was, for the first time in his life, financially well off. His London agent, Samuel Stevens, had invested his money from the collection sales well in East Indian Railway shares. However, over the next several years Wallace lost his savings through a series of bad investments and needy relations. This part of Wallace's life is particularly well documented in Peter Raby's fine biography of Wallace from 2001. Wallace tried unsuccessfully several times to secure full-time employment. Instead he earned money by writing, occasional lectures and finally, in the only regular paid job of his latter life, correcting exam papers each year.

In 1864 Wallace was devastated when his fiancée suddenly broke off their engagement. "I have never in my life experienced such intensely painful emotion" he wrote. A few months later, in 1865, he began attending spiritualist seances. Like mesmerism and phrenology before, Wallace thought he approached the subject with scepticism but soon became entirely convinced that the "phenomena" produced by mediums such as table rappings, spirit writings, apparitions in dark rooms and so forth must be genuine and never again doubted his conclusion. The following year he published 'The scientific aspect of the supernatural' (1866) urging that spiritualism merited scientific investigation. Few of his scientific contemporaries agreed.

Near the end of 1864 Wallace met Annie Mitten, the daughter of his botanist friend William Mitten. The couple were married in 1866. They had three children, two of whom survived to adulthood.

In 1869 Wallace published his most famous book, The Malay Archipelago, recounting his travels in Southeast Asia. It continues to enthral readers with its tales of adventure and a deep appreciation for tropical natural history.

In 1869 Wallace published his most famous book, The Malay Archipelago, recounting his travels in Southeast Asia. It continues to enthral readers with its tales of adventure and a deep appreciation for tropical natural history.

In this wonderful book, Wallace popularized his famous generalization of an dividing line between the very different faunas of Australia and Asia, now known as the Wallace Line. "We have here a clue to the most radical contrast in the Archipelago, and by following it out in detail I have arrived at the conclusion that we can draw a line among the islands, which shall so divide them that one-half shall truly belong to Asia, while the other shall no less certainly be allied to Australia." The book was also heavily anthropological, focusing on the races, languages and other cultural details he observed.

It has become a commonplace to state that this book has never gone out of print. This is incorrect as shown in the definitive edition The Annotated Malay Archipelago (2015). The book ceased publication in 1922 and was only republished again in 1962.

Also in 1869-1870 Wallace published new notions about the origins of human beings which marked one of his greatest theoretical departures from Darwin. (Wallace 1869, Wallace 1870: 332-371) Wallace could not see how natural selection could bring about several attributes of human beings, such as a moral sense and great intelligence, because he assumed these were not needed by 'savage' peoples in a wild state. Instead, he claimed, an overruling supernatural intelligence must have intervened in human evolution.

In the 1870s Wallace returned to his earlier interests in biogeography. In 1876 he published one of his most important books: The geographical distribution of animals. Following the work of Philip Lutley Sclater (1857) Wallace divided the world into six main regions. Wallace discussed the factors which determined the dispersal of living and extinct terrestrial animals including elevation, vegetation, land bridges, ocean depth and glaciation. In recent years it has become a commonplace to call Wallace the founder of biogeography. This is quite incorrect and deeply historically ignorant. For decades many authors had written about biogeography before Wallace. It is unfortunate that so many writers have repeated this and other false claims about Wallace.

Wallace's book Tropical nature and other essays (1878) was mostly reprinted material. It included Wallace's response to Darwin's theory of sexual selection to explain the origin of animal colouration. Wallace argued that endless reiterations of female choice could not bring about male colours and structures, as Darwin argued, for example, for the feathers of the Argus pheasant. Instead Wallace proposed that the "greater vigour and activity and the higher vitality of the male" led to more vivid colouration.

In 1870 Wallace took up the published wager of a flat Earth advocate to prove the Earth is round. Wallace demonstrated, using his old surveying skills, that a six mile stretch of the old Bedford canal was indeed slightly curved and not flat. But his opponent refused to accept the results and spent the rest of his life libelling and persecuting Wallace. Such are the consequences of vexing a madman with no decency or principles! It was, Wallace recalled, "the most regrettable incident in my life" and "cost me fifteen years of continued worry, litigation, and persecution, with the final loss of several hundred pounds."

Wallace's book Island life (1880) marked a return to writing about scientific matters after something of a hiatus and was one of his most successful. It surveyed the problems of the dispersal and speciation of plants and animals on islands which he categorized, following Darwin, as oceanic and continental. The latter type Wallace subdivided into "continental islands of recent origin", like Great Britain, and ancient continental islands, such as Madagascar. Unlike Darwin's theories of erratic spread to account for the discontinuous distribution of types, Wallace favoured theories of continuous spread followed by selective extinctions which resulted in the appearance of gaps.

After 1880 Wallace's attention was increasingly spread amongst ever wider areas including a land nationalization campaign, his passionate anti-vaccination campaign, urban poverty, socialism, private insane asylums, militarism and life on other planets.

From 1886-1887 Wallace travelled on a lecture tour across the United States of America. Darwin had died in 1882 and his death and legacy had been discussed in thousands of publications around the world. During his tour, Wallace was hailed as a great innovator since he was the co-originator of natural selection with Charles Darwin.

From 1886-1887 Wallace travelled on a lecture tour across the United States of America. Darwin had died in 1882 and his death and legacy had been discussed in thousands of publications around the world. During his tour, Wallace was hailed as a great innovator since he was the co-originator of natural selection with Charles Darwin.

The modern creationist movement had not yet arisen. His lectures outlined the theory of evolution by natural selection and the evidence that supported it. These lectures formed the basis of one of his most important books, Darwinism (1889). The book was perhaps the clearest and most convincing overview of the evidence for evolution produced in the nineteenth century, next to Darwin's On the origin of species, and remains an outstanding overview even today. Wallace was more strictly selectionist than Darwin, who allowed roles for other causes of change. However, Wallace's supernatural speculations regarding mankind's origins in the final chapter 'Darwinism applied to man' were either ignored or lambasted by contemporary reviewers. Some of the harshest words ever published about Wallace, in fact, were in reference to this chapter. The physiologist George John Romanes wrote: "It is in the concluding chapter of his book, much more than in any of the others, that we encounter the Wallace of spiritualism and astrology, the Wallace of vaccination and the land question, the Wallace of incapacity and absurdity." The accusation of belief in astrology was incorrect. This attack led to an ugly dispute between the two men and in their exchange of letters, Wallace revealed that he had made copies of some of Romanes's private letters about spiritualism that had been shown to him. This surprising episode is well covered in Ross Slotten's 2004 biography of Wallace, one of the vanishingly few to treat Wallace neutrally and historically and not as a genius hero-victim to be praised and promoted.

Wallace's book The wonderful century (1898) discussed the achievements of the nineteenth century and, at far greater length, its problems. Land nationalisation (1882), was a handbook on land reform aimed at informing the "landless classes" how to recognize what Wallace saw as their rights regarding land ownership: "to teach them what are their rights and how to gain these rights".

His book Man's place in the universe (1903), argued against beings existing on any other planet in the solar system (particularly given recent speculation about Mars) or indeed anywhere else in the universe but Earth.

In 1905 he published his lengthy two volume autobiography My life. It remains the principal biographical source on Wallace. A condensed edition appeared in 1908.

The world of life (1910) was Wallace's final word on spiritualism and his view that humanity was placed on Earth for a supernatural reason. His last two books were on social issues and the land question. Social environment and moral progress and The revolt of democracy, appeared in 1913. The "land monopoly and the competitive system of industry" were the two fundamental causes of poverty and starvation in a land of superfluous wealth. Here again was Wallace's conviction that removing social obstacles would allow the inherent progress of natural laws to ensue.

Wallace died peacefully in his sleep at the age of 90 on 7 November 1913. The year 2013 was therefore the centenary of Wallace's death and saw many events and publications around the world to commemorate his life and work. In his latter years, as a rare surviving principal player in the Darwinian revolution, he was heaped with honours which he neither sought nor particularly wanted.

The historical Wallace vs. the modern myth

In recent times it has become a popular sound-bite to claim that Wallace's was the most famous scientist in the world when he died because many interviewers and obituarists called him 'our greatest naturalist' and such. As polite and honourable as those writers were, the claim that he was the most famous scientist in the world or one of the most famous persons is simply ridiculous. Wallace was nowhere close to being the most famous scientist in the world and all accredited historians of science of the period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries regard the claim as laughable. It is no fault of Wallace, and does him no discredit, that the fanciful claims of modern fans about him are historically inaccurate.

Only in the mid-twentieth century did the image of Wallace familiar to readers today emerge- that he is supposedly strangely forgotten or that he was cheated, robbed or in any way unfairly treated or that there is something one ought to regret or feel sorry for in his story. The Wallace in modern writings is a dramatic departure from the historical Wallace described by himself, his contemporaries and writers for half a century after his death. In the writings of conspiracy theorists and sympathetic amateurs, Wallace has become instead a mythical hero-victim whose legacy must be set right. And yes Wallace was was not and is not a victim, his lack of wealth or social standing had nothing to do with his fame in his lifetime or after, he was not the founder of biogeography (which existed before his birth) and his theory of evolution was not the same as Darwin's. The two common denominators in modern myths about Wallace are 1. to exaggerate his disadvantages and hardships (such as forced to leave school early) and 2. to exaggerate his heroic greatness.

Indeed these themes are so powerful that to question or debunk any of the historically inaccurate claims about Wallace is treated with cult-like ferocity. Ironically, the most militant Wallace fans denigrate, defame and persecute any critics far worse than anything Wallace supposedly suffered.

The real Wallace remains an endearing, colourful, confusing and controversial figure in the history of science. But above all he remains an inspiration as someone from an ordinary background who, without the advantages of wealth or connections, could achieve extraordinary things through hard work, enthusiasm and independent thinking.

To find out more about Wallace see:

John van Wyhe, 2020 A. R. Wallace in the light of historical method. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 103: 89-95.

John van Wyhe, Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the discovery of evolution by Wallace and Darwin. WSP, 2013.

John van Wyhe ed., The Annotated Malay Archipelago by Alfred Russel Wallace. NUS, 2015.

John van Wyhe & Kees Rookmaaker eds., Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago. Foreword by Sir David Attenborough. OUP, 2013.

'Island Adventurer: Alfred Russel Wallace' an animated film by Science Centre Singapore.

Wallace's autobiography: My Life and Wallace letters and reminiscences.

Wallace items in Darwin Online

John van Wyhe, 2014 A delicate adjustment: Wallace and Bates on the Amazon and "the problem of the origin of species". Journal of the History of Biology 47, 4: 627-659.

John van Wyhe & G. Drawhorn, 2015 "I am Ali Wallace": The Malay assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Society 88, Part 1, No. 308 (June): 3-31.

John van Wyhe, 2016 The impact of A. R. Wallace's Sarawak Law paper reassessed. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 60, Dec., pp. 56-66.

John van Wyhe, 2016 A rough draft of A. R. Wallace's "Sarawak law" paper. Archives of natural history 43.2: 285-293.

Kees Rookmaaker & John van Wyhe, 2018 A price list of birds collected by Alfred Russel Wallace inserted in The Ibis of 1863. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 138 (4): 335-345, fig. 1 (with Kees Rookmaaker).

John van Wyhe, 2018 Wallace's help: the many people who aided A. R. Wallace in the Malay Archipelago. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (June) 91, 1, 314, pp. 41-68.

John van Wyhe, 2020 A.R. Wallace in the light of historical method. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 103, pp. 89-95.

Kees Rookmaaker & John van Wyhe, 2024 Shared experiences of Alfred Russel Wallace and Hermann von Rosenberg in exploring the ornithology of New Guinea and the Aru Islands in 1858–1860. ARDEA 112(2): 323-330 (+5pp. supplementary)